AU summit reflects fractured state of Africa

If the success of a summit was measured by the number of police and army of the host country deployed to guard the visiting heads of state from a score of African countries, the 31st Africa Union summit in Mauritania must be deemed a success.

A new and very costly conference centre, endless four-wheel drive vehicles buzzing around town and a very busy agenda and weighty subjects — the creation of a free trade zone officially launched in March, debates about corruption, the financial independence of the African Union — suggest an important meeting. Yet the absence of many important heads of state — from Egypt, South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, Morocco and Angola — adds a note of caution.

French President Emmanuel Macron visited Mauritania during the summit but his focus was on meeting the heads of state of countries that belong to G5 Sahel group, which, together with France, has committed troops and money to improve security in the Sahel.

A suicide attack against the headquarters of the G5 force in Mali before the summit reminded delegates that the security of the Saharan belt has not improved despite considerable French-led military efforts to roll back attacks. The flaring of violence in Libya and Tunisia can only comfort the view from further afield that north-west Africa is in a sorry state.

Macron’s visit was motivated by a further consideration — trying to convince Africans to stay home.

Despite the drop in numbers of Africans trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe, the very question of African migrants to Europe has produced a perfect storm in Europe and is the number one question on the minds of French and Italian electors. The failure of the European Union to find a common policy on migration fuelled the rise of populist parties across Europe that are happy to mix terrorism, immigration — illegal or not — and a whiff of racism in their attempt to close the door on Africa.

Some issues, however, are too delicate it seems for an African summit to address: corruption, which sucks away huge sums of money from the continent every year and the fact that migrants are not the poorest of Africans, rather those who are educated and seeking greener pastures.

The United States’ secret wars in Africa simply figure nowhere yet they pose questions: Is the answer to Africa’s woes simply to “fight terrorism” or should more effort and money not be put into economic development and consolidating the rule of law? How can a continent develop if it loses an estimated quarter of the wealth it creates annually to investment by its elites in other continents?

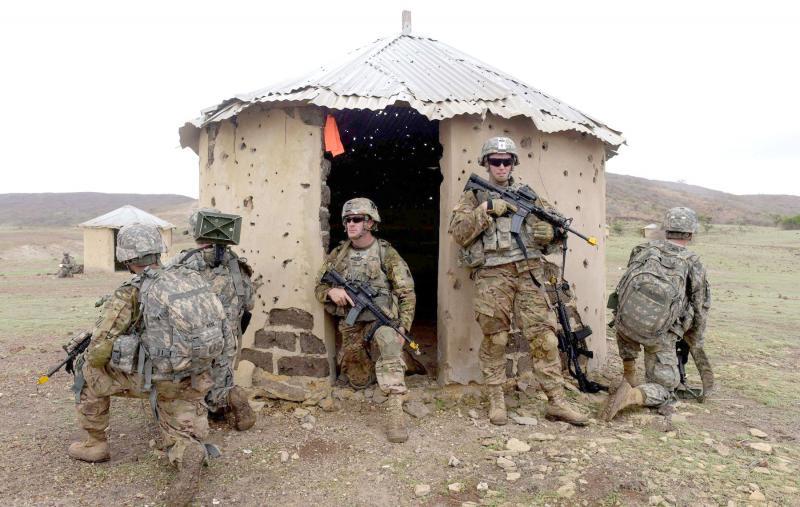

Secret programmes in Washington allow US troops to direct combat raids in Somalia, Kenya, Niger and other African countries. The Trump administration — as did Barack Obama’s — has allowed the US military to rely on partners in African countries to carry out missions against suspected terrorists, to avoid casualties after years of massive direct involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What happens essentially is that African governments loan out units of their militaries for US commando teams to use as surrogates to hunt militants identified as potential threats to US citizens and interests. That is instead of having the US commandoes help the African troops accomplish their own objectives, as other US specials operation teams do in Africa.

As the Pentagon refuses to acknowledge the full nature of its mission in the Sahel, it is impossible to piece together the full extent of US involvement. The annual funding for these programmes in Africa is $100 million. The US Congress has reauthorised temporary authority every year until last year when the lawmakers made it permanent.

Though US commanders try to keep American troops out of direct combat if possible, US policy illustrates the murky nature of who is assisting whom in Africa, say former Pentagon officials who oversaw counterterrorism policy in north-west Africa.

The fractured state of Africa, the fact that many conflicts are a complex overlay of tribal/politics fights going back decades, smuggling of weapons, cigarettes and cocaine, as well as disputes arising from every greater drought hardly suggest this is an easy fight to win. What it does suggest, however, is a huge morass of overlapping and not always well-informed decisions.

The French at least have known the Sahel region for more than a century, the United States not. The impression some observers of the region have is of a fuite en avant with no exit strategy. Only time will tell.

Francis Ghiles is an associate fellow at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.