China’s Middle East policy runs into problems

China’s rise to the rank of major world power has mostly been on its own terms. That is true considering this rise from an economic standpoint but it has also been true in the country’s foreign policy.

In recent years, however, especially in the Middle East, Beijing’s major source of crude oil, but also among the Muslim countries of Asia, China’s discombobulation has shown up in several incidents. Potentially, the most serious is the detention of an estimated 1 million Chinese Muslim Uighurs in re-education camps in the country’s north-western province of Xinjiang. That could be a black swan with serious consequences for China’s foreign policy.

The wall of Muslim silence is beginning to crack on the harsh repression of the Uighurs. Anti-Chinese feelings are rising in neighbouring Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, where the forced assimilation of Muslims across the border feeds feelings of guilt and helplessness.

Protests have occurred in Bangladesh and India while critical articles appeared in Pakistani media. As Germany and Sweden banned the deportation of Uighurs who have taken refuge there, the Trump administration is considering Xinjiang-related sanctions. Senior political figures in Malaysia have become the first in a Muslim country to condemn China’s policy. That puts pressure on Turkey (the Uighurs speak a Turkic-related language) and Saudi Arabia.

China has created its first foreign military base in Djibouti and its growing portfolio of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments speaks of a growing military presence overseas. Chinese leaders might be comfortable with the idea of exporting their own model of the surveillance state to other autocrats but blowback could come from unexpected places.

As China builds and manages a port in Gwadar, Pakistan, it risks “inadvertently embarking on its own colonial adventure in Pakistan — the biggest recipient of its BRI investment and once the old East India Company’s old stamping ground,” said the Financial Times’ Jamil Anderlini.

He said Pakistan is “virtually a client state of China. Many within (Pakistan) worry openly on its reliance on Beijing, (which) is already turning it into a client state… It is easy to envisage a scenario in which militant attacks on Chinese property overwhelm the Pakistani military and China decides to openly deploy the People’s Liberation Army to protect its people and assets.”

China knows that an economically driven approach is no magic wand. In 2011-12, China had to rescue 35,000 of its citizens from Libya and its establishing parallel relations with the opposition National Council did not save it being identified with the old regime. That evacuation was the first of similar ones in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Chinese workers have been kidnapped in South Sudan and the Sinai.

What worries China is that Uighurs and Chechens joined jihadists in Syria and Libya. China has certainly changed the world but seems to be slow in understanding that it has also changed the world’s view of China.

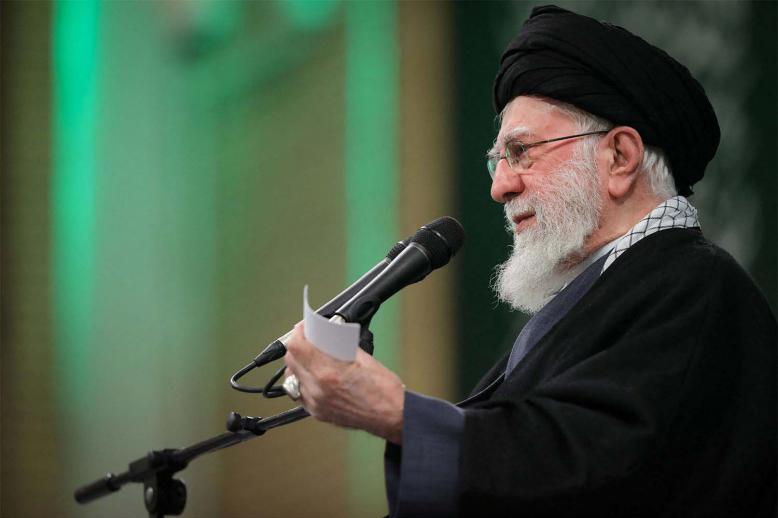

Not only will it find it increasingly difficult to remain on the sidelines of the multiple conflicts that beset the Middle East but it can only blame itself for the fallout of a campaign in Xinjiang that challenges the fundamentals of the Islamic faith itself. This campaign is very different from past incidents, including Iranian Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie’s novel or the 2006 Muslim boycott of Danish products because of controversial cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammad.

The camps China set up have led, a recent US congressional report stated, to the “largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.” China’s “strike hard” campaign is using extrajudicial detentions, surveillance, political indoctrination, torture and abuse to root out extremist elements, a report in the Guardian, a British newspaper, stated. As many as 1.1 million people — about 10% of Xingjian’s adult Muslim population — have been detained in re-education camps, the NGO Chinese Human Rights Defenders and Equal Rights Initiative estimates. A recent Human Rights Watch reports offers a detailed account of how internees are mistreated.

How convenient for the Chinese authorities to present all Uighurs as hard-line supporters of al-Qaeda. Chinese policies, which are deeply racist, are the best way to radicalise the Uighurs. As much as Chinese authorities protest mounting evidence that suggests its crackdown in Xinjiang is a perfect black swan.

As the old Great Game played out in the 19th century in Central Asia between the Russian and British empires is being revived, this time with multiple players, it will be difficult for China to stay on the sidelines of the conflicts. China’s harsh repression of the Uighurs could well show the limits of the country’s traditional foreign policy as it gets entangled in its repressive domestic policy towards Muslim Turkic people.

Francis Ghiles is an associate fellow at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.