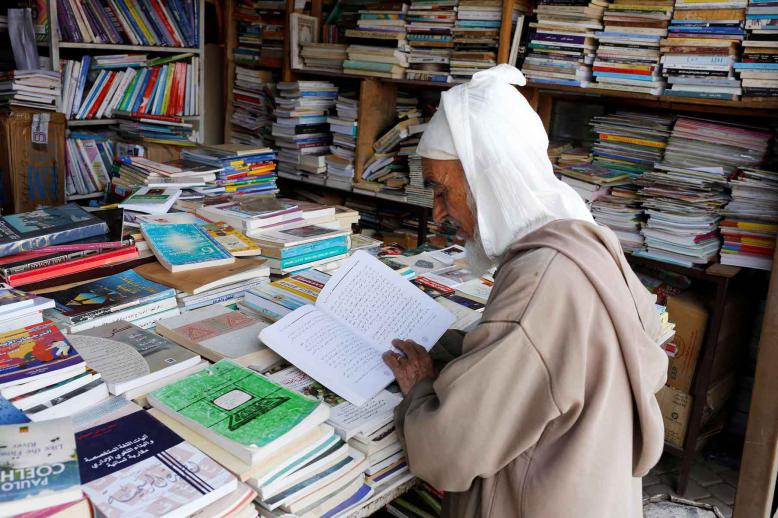

Do dialects threaten or nourish Standard Arabic?

CAIRO - In nearly every modern novel in Standard Arabic there is bound to be dialogue written in dialectical Arabic. This style feature feeds the feud between supporters of the sole use of Standard Arabic and those who favour injecting local dialects.

Even though a new round of the battle is taking place, the feud itself dates to the 1950s. The debate rages on, especially after some juries in literary competitions in the Arab world said they would have accepted the use of dialects in novels.

Standard Arabic purists said it can be used to express many situations and attitudes shared by all Arabic speakers. Therefore, it is essential to preserve it to elevate artistic and literary taste.

Defenders of dialects in literature say that using “popular” dialects introduces realism. As far as comprehension is concerned, this side of the debate argues that satellite TV channels have made it possible for Arabic speakers everywhere to understand local dialects.

For defenders of Standard Arabic, 1988 Nobel Prize Literature Laureate Naguib Mahfouz is the best example supporting their argument. Mahfouz, born in Cairo, wrote realistic novels using only Standard Arabic, even in dialogues.

In Syria, the late novelist Hanna Mina shared Mahfouz’s commitment to Standard Arabic in literature and succeeded in depicting daily life and characters in Syrian society using Standard Arabic.

Perhaps the best-known supporter of the use of local dialects in all forms of communication is late Egyptian intellectual Louis Awad, who used Egyptian Arabic in his writings and organised several campaigns to encourage using dialects in narration and not just in dialogues.

As it often happens in such feuds, the debate is not purely about language usage. Purists accused supporters of the dialects of wanting to destroy Classical Arabic. They accused them of a lack of respect for its rich literary heritage.

Champions of the dialects have accused purists of closed-mindedness and of wanting to have patriarchal control of Arabic literature.

With new generations of novelists and writers in Arabic, the balance of power has shifted in favour of the modernist camp. Local dialects have become the staple of dialogues in novels. In some cases, the dialect used is so geographically restricted to specific communities like the dialects of Southern Egypt, of Aleppo in Syria, Shawia in Algeria and Kurdish in Syria and Iraq.

Virtual reality and social media platforms add a twist to the debate. Youthful users have developed a specific style of mixing Standard Arabic with foreign words in their communications. That style has found its way to dialogues in novels. It is not uncommon to find main characters in modern novels in Arabic using words and expressions such as “missed call,” “delete,” “block” and “chat” and those words would appear written in Arabic characters.

Supporters of the dialects argue that novelists should depict reality as closely as possible. They argue that Standard Arabic is flexible and has evolved with daily life.

Yasser Ramadan, head of Kunuz Publishing House in Cairo, said the Arab world has become familiar with local dialects of Arabic. He said using dialects in novels in Egypt gave them more realism and credibility. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Telegram, have allowed Arab intellectuals to communicate with each other and understand each other even when local dialects are used.

The purists’ argument is alarmist. They fear that too much reliance on dialects in dialogues will lead to abandoning Standard Arabic altogether.

Egyptian novelist Nasser Arak said: “Resorting to dialects in novels or at least in the dialogues between the characters of the novel is absolutely undesirable. Using the dialect simply weakens the quality of the literary text beyond repair.”

“True literature must be based on established and known language rules. A talented writer would be able to get inspired by these rules and improve them. Dialects, however, have no specific rules and therefore are quite poor to be able to provide the specific qualities of a good literary text,” Arak added.

Standard Arabic has codified rules that have been stable for centuries. A talented, sagacious writer can tap into the hidden powers of the language. The best example is again Mahfouz. In his novels, beggars, informers, bootlickers, prostitutes and street vendors speak in a simple and yet subtle Standard Arabic.

Critics and writers are trying to find a middle ground. They insist that the fundamental principle in literary writing should be freedom of creativity. The theory behind the “middle-grounders” is that Standard Arabic is one way Arab unity is maintained. A “middle language” between Classical Arabic and the dialects — the so-called “Third Language” — is possible and would reconcile Classical Arabic with modern times.

Algerian writer and translator Younes Amara said he has no problem with using dialects in novels. He does, however, have reservations about translating foreign works straight to dialects.

He pointed out that valuing dialects and pushing them as alternatives to Standard Arabic in all domains mean that dialects would be considered full languages and could lead to their codification.

“If promoters of dialects discover this particular point, they would immediately realise that that process would spell certain death for any dialect,” Amara said.

Mustafa Abid is an Egyptian writer and journalist.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.