Iran’s ‘hybrid nationalism’ has implications for Iranian politics

After “America First” comes “Iran First.” In its official response to US President Donald Trump’s decision to reject the US commitments under the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers, Tehran denounced “Trump’s absurd insults against the great Iranian nation.”

The statement, issued by the Foreign Ministry, asserts that “the people of Iran will, with calm and confidence, continue their path towards progress and development.” It lauds Iranians as “brave and civilised people” and says Iran is “a trustworthy and committed partner for all who are prepared to cooperate on the basis of shared interests and mutual respect.”

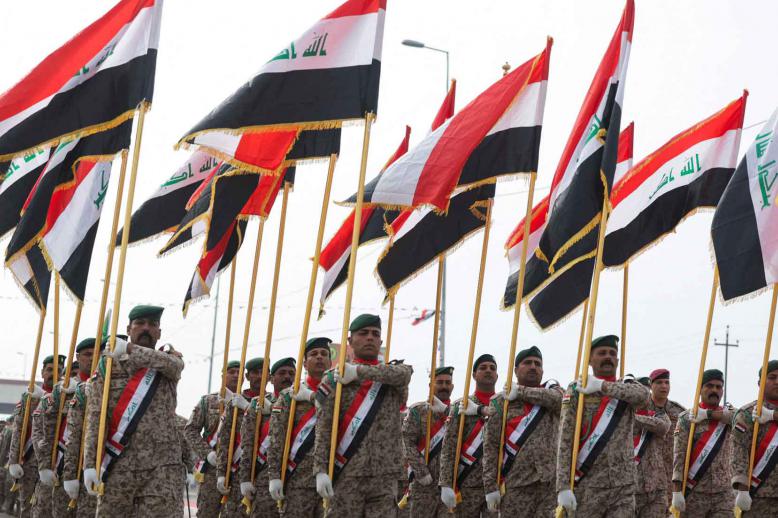

Analysts have identified a growing use of nationalist sentiment by Iran’s leaders. On April 18 — Army Day — the annual parade of the armed forces echoed for the first time since the 1979 revolution to “Ey Iran,” which is often seen as an alternative to the official anthem of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

“’Ey Iran’ was composed in 1944 by Ruhollah Khaleqi, with lyrics by Hossein Gol-e Golab, and was first performed and recorded by the iconic Iranian singer Gholam-Hossein Banan,” said Nima Mina, senior lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. “Neither Khaleqi nor Gol-e Golab nor Banan had any known ideological affinity with Iran’s Islamists. Since 1979, ‘Ay Iran’ is often played in gatherings inside and outside Iran by Iranians who don’t recognise the official anthem as their own.”

Mina said the use of “Ey Iran” is a “sign of desperation.” He said Tehran’s propagandists are “aware that sectarian religious propaganda splits Iranian society and has no potential to mobilise the regular armed forces, let alone the population at large.”

The relationship between dynasties, religion and nation in Iran is a long, complex one. Historians agree that the 1979 Islamic Revolution emphasised religion rather than nation but, in general, Iranians remain nationalistic and effortlessly juggle the lunar Islamic calendar and a solar Iranian calendar, marking the festivals of both.

This makes for considerable cultural variations, a subject recently addressed by Saeid Golkar, visiting assistant professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Golkar’s paper, published by the Washington Institute for Near-East Policy, is titled “Cultural Heterogeneity in Post-Revolutionary Iran.” It argues Tehran faces a cultural conflict between “religious-Hezbollahi” and “hybrid post-modern” worldviews. The post-modernists, who are generally young, believe liberty is as important as religion. They meet in coffee houses rather than religious centres, but are not necessarily secularists and may even embrace a rising wave of Sufism.

Within the religious camp, Golkar points out the differences between the Hezbollahis and traditionalists. The Hezbollahis support velayat-e faqih, the constitutional principle giving pre-eminence to the supreme leader. The traditionalists are sceptical of politics and may follow Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the Iranian-born Najaf cleric, rather than Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader.

Golkar traces divisions to the keeping, or not, of pet dogs and the names chosen for offspring. Those with a religious world-view pick Ali and Fatima. Post-modernists choose Cyrus and Nazanin.

Golkar suggests the Iran’s leadership could broaden its support base through a “hybrid nationalism” that could use the “Ay Iran” anthem. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, president for eight years from 2005, was difficult for Khamenei to manage, but many of his actions and rhetoric showed the appeal of nationalism.

Golkar said turning to “hybrid nationalism” would be hard with Khamenei in power. “The first generation of Revolutionary Guard leaders, like Fadavi, don’t like nationalism,” he said, in a reference to Rear Admiral Ali Fadavi, commander of the Revolutionary Guard Navy. “Ayatollah Khamenei has the same idea: Nationalism goes against his notion of Islamic civilisation. A majority of the clergy are naturally not nationalist. But the younger swathe of Guards, and clerics, are more pragmatic. Many activists admire [Russian President Vladimir] Putin as a strong leader who scares the West.”

The challenge posed by hybrid nationalism was recently illustrated by the apparent discovery of the remains of Reza Shah in Tehran. “The family wants the body returned, while Iranian nationalists want it buried where they can visit the ‘father of modern Iran’,” said Golkar. “Hardliners want it destroyed or buried secretly.”

Iranian nationalism could be an easier option, then, for Iran once the 78-year-old Khamenei is gone and a new supreme leader is in place but is that soon enough?

Golkar is unsure. “Crises can accumulate. Imagine a hot summer. Already with the lowest rainfall for 15 years, Isfahan is cutting water supplies. In hot weather, the morality police are on the streets looking for ‘bad hijab,’ which widens the cultural gap [between conservatives and liberals],” he said.

“To stay powerful, the leaders of the Islamic Republic have to adjust their relationship with society. Imagine if someone like Qassem Soleimani [al-Quds force commander] or Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf [former Tehran mayor] visited the tomb of Cyrus the Great [ruler 600-530BC] and talked about being Iranian and Muslim and about Iran’s glorious past. This would be popular even with secular nationalists.”