Iran facing its ‘biggest crisis’ 40 years after revolution

ISTANBUL— As Iran marks the 40th anniversary of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s revolution, the Islamic Republic is caught in the most serious crisis of its history and could face collapse if it avoids fundamental reforms, observers said.

“Today the country is facing the biggest pressure and economic sanctions in the past 40 years,” Iranian President Hassan Rohani said during a ceremony at the shrine of Khomeini.

Rohani blamed sanctions reimposed by US President Donald Trump, who was attempting to force Tehran to agree to tighter rules for its nuclear programme, for the difficulties. “The Islamic system should not be blamed,” he added.

Many Iranians beg to differ.

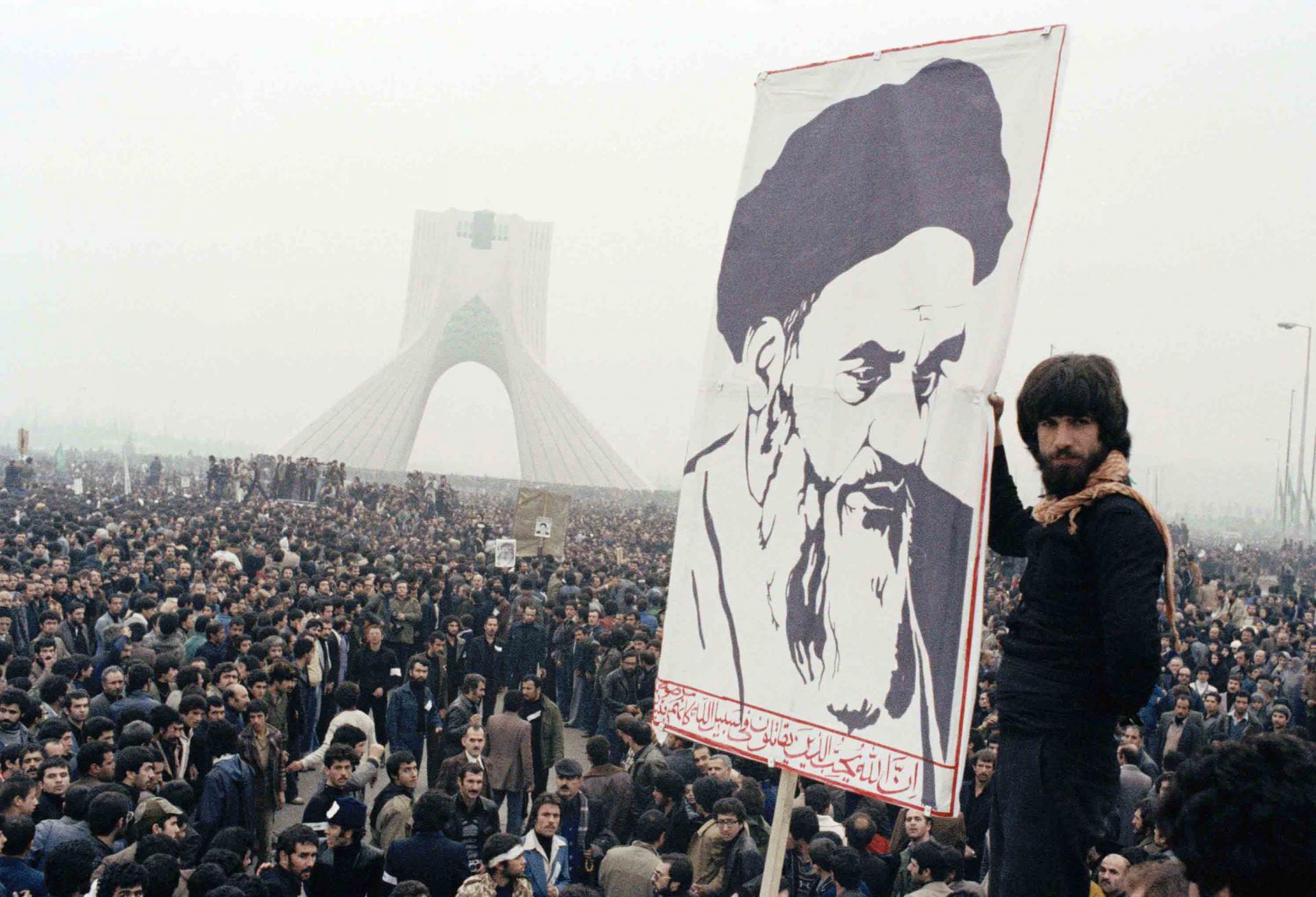

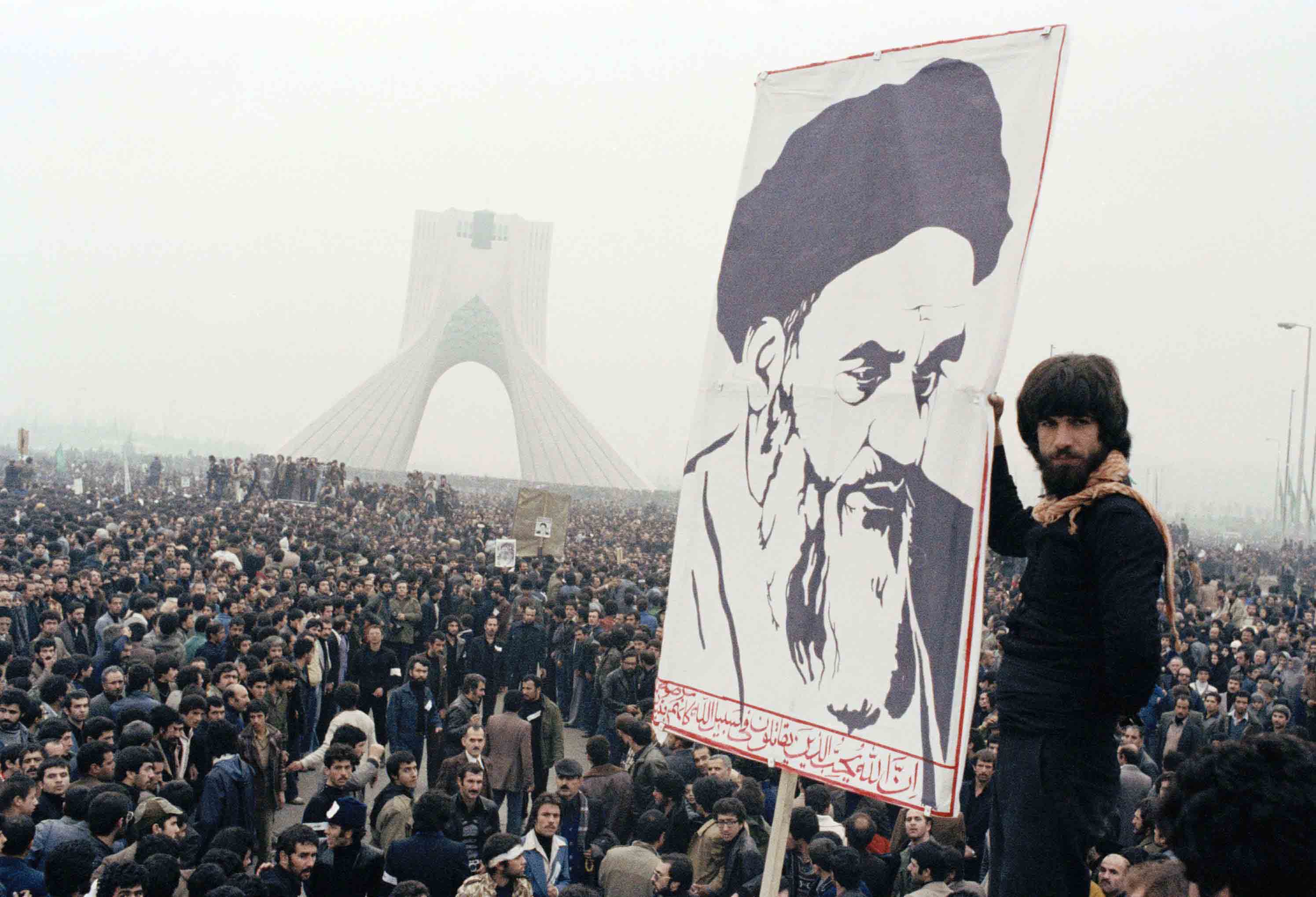

When Khomeini returned from exile in France on February 1, 1979, he vowed to build a just order based on Islamic values. Ten days later, the government of Shah Reza Pahlavi collapsed.

However, 40 years on, disillusionment has set in and many Iranians complain about economic mismanagement, corruption and an unresponsive political system in a country of 80 million people that sits on some of the world’s richest oil and gas reserves.

Abolhassan Banisadr, Khomeini’s first president, accused the leader of the revolution of betrayal. He told Reuters that Khomeini had committed himself to democratic principles and human rights during his exile but ignored those promises after his return. “For me it was a very, very bitter moment,” Banisadr said, adding that Iran was a “dictatorship” today.

Since Trump’s sanctions kicked in last year, workers, including truck drivers, farmers and merchants, have carried out sporadic protests against economic hardships. The demonstrations have occasionally led to confrontations with security forces.

Opposition to the United States, called the “Great Satan” by Iranian officials, has been a tenet of the Islamic Republic since its inception. Many Iranians were wary of the Americans because of the US coup against Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953 and because of Washington’s support for the shah and alleged US help for a possible counter-revolution that led to the seizing of the US Embassy in Tehran in 1979 and the hostage crisis that lasted until January 1981. Diplomatic relations remain cut.

Iran’s vow to export its dynasty-toppling revolution deepened the confrontation with the West and adversaries among the monarchies and other governments in the region. Support for Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthi rebels in Yemen demonstrated to other players that Tehran was bent on establishing a “Shia Crescent” from Iran via Iraq and Syria towards the Mediterranean.

The nuclear deal of 2015 allowed Iran to emerge from international isolation but Trump’s announcement last May withdrawing from the agreement meant that sanctions designed to cripple Tehran’s vital oil exports returned with a vengeance. Trump called Iran the “world’s leading state sponsor of terror” and a “corrupt dictatorship” in his State of the Union speech February 5.

Tehran’s efforts to cushion the effects of the US sanctions have only been partially successful. Suspected Iranian terror plots against dissidents in Europe undermined efforts by the Iranian government to shield its relations with EU counties that oppose Trump’s decision but are wary of Iranian activities within their borders.

As a result, the economic progress that Rohani had hoped for has not materialised. A currency crisis, a private sector stifled by state enterprises or companies with links to the military, a wobbly banking sector and a scarcity of foreign investment block development. The International Monetary Fund is expecting the Iranian economy to contract 3.6% this year.

Some observers say more unrest could spread and further shake the regime. “There is a potential for a working-class movement that could put pressure on the government in unprecedented ways,” said Arash Azizi, a New York-based writer on Iranian affairs. “There is a tradition for this: In 1979, the deadly strike against the shah regime came from protesting oil workers.”

Farhang Jahanpour, an Iranian academic and member of Kellogg College at the University of Oxford, said the regime will have to tackle key underlying problems if it wants to survive.

“The Iranian political and religious establishment must make some drastic changes in its ideology, system of government and domestic and foreign policies if it hopes to escape major social upheaval leading to the possible collapse of the system,” Jahanpour wrote in an analysis for the foreign policy blog LobeLog.

“Iran should learn from the experience of the Soviet Union and other revolutions that collapsed because they failed to respond to the demands of their people,” he added.

Jahanpour singled out the “velayat-e faqih or the guardianship of the clerics,” a core principle of Khomeini’s system, as an area that had to change. “Iran’s young generation does not need clerical guardians,” he said.

Thomas Seibert is an Arab Weekly contributor in Istanbul.

Copyright ©2019 The Arab Weekly — distributed by Agence Global