Moustaches and magical realism in Ba’athist Syria

Rana Haddad doesn’t exactly balk at the suggestion that her first novel, “The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor,” is an example of “magical realism” but she’s a writer who resists the classification of genre.

“I was consciously trying not to write anything that wouldn’t happen in real life,” she said. “It’s magical but it’s playing with your mind rather than someone flying or really strange things happening.”

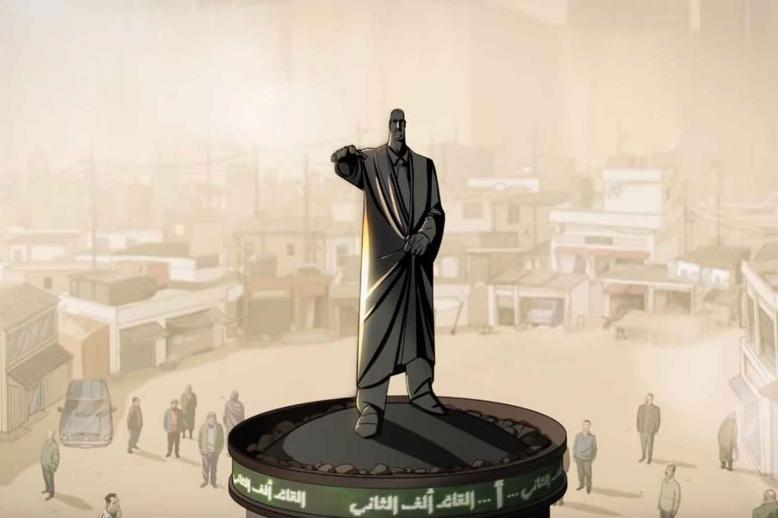

This playfulness develops as Dunya Noor, daughter of an eminent Latakia heart surgeon and a blonde English mother, defies her father by pursuing a career as a photographer and by taking up with an unsuitable would-be astronomer of lower rank. The setting, the book’s title page explains, is the end of the last century, “when a moustachioed military dictator, with an abnormally large head, named Hafez Assad… ruled Syria.”

The satire cuts along a wafer-thin line from credibility. Returning from abroad, Noor tells a suspicious airport security man that her camera isn’t the kind used by a spy, who would have one concealed in a pen or briefcase.

“They are paranoid but in reality these things do happen,” Haddad said. “There are spies, it’s not only paranoia… I’m trying to show that something is funny and a little bit sad — and that it can become evil or dangerous.”

Hence the chapter “Mustache Power” explores a symbol of patriotism. “A lot of men in the Ba’ath Party did have these moustaches, more of a modernist moustache than the traditional one,” she said.

Haddad left Syria for the United Kingdom at the age of 15 with no English and yet, some three decades later, has written a novel set in Aleppo and Latakia in English rather than Arabic.

“In English you feel under pressure to write in a particular way, which doesn’t reflect how I am, my soul or something, which is Arabic,” she said. “I found it difficult to translate my inner self into English. I kept trying and it developed slowly. When I was looking at Arabic literature in English, it is quite sad and I couldn’t relate to that any more than I could to English contemporary writing. I felt a little at sea.

“Arabic gives you access to another world view that is very poetic and quite philosophical. Older English — Shakespeare or the Romantic poets — is along the same lines, but more contemporary English writing has entered a more rational space, and there is more cynicism.”

This can’t be reduced to style or fashion. “In English, the word often means itself, it doesn’t usually have a philosophical root,” she said. “In Arabic, many words convey a deep meaning. The word ‘darkness’ [‘thalam’] in Arabic has the same root as ‘injustice’ [‘thulum]’. ‘Darkness’ is not just physical, it is emotional and spiritual and then it becomes ‘injustice’ in behaviour.”

Aside from politics, “The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor” plays with light and dark in astronomy and photography. As the plot twists, it questions black-and-white assumptions about gender not just with Noor’s choice of career (“Only an Armenian would think photography is a career,” says a friend of her father, “that and hairdressing”) but with a splash of cross-dressing.

“This wasn’t conscious,” Haddad said, “but I realised at the end of the book I was showing conflict on all levels and then trying to find a way of bringing things together.”

Haddad celebrates difference and reconciliation. “In Syria you have an Islamic tradition but it’s connected to the pre-Islamic tradition — not just the Christian and Byzantine but before that, all the ancient layers — where there is veneration of femininity: The earth is fertile, the city is a woman, there’s a connection to the feminine powers. The men are very tuned in, they love food, they’re interested in things that in England would be considered feminine. If you take that awareness away, it makes daily life very dull,” she said.

Gareth Smyth has covered Middle Eastern affairs for 20 years and was chief correspondent for The Financial Times in Iran.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.