Al-Sadr’s strong electoral showing puts US in quandary

The strong showing by Muqtada al-Sadr’s coalition, called the Sairoon bloc, which won the plurality of votes in Iraq’s parliamentary elections, is causing heartburn in Washington, though his anti-Iran stance is mitigating the concern.

Most of that heartache comes from memories of the years after the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq when al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army battled US troops in Baghdad and southern Iraq, causing hundreds of American casualties. At the time, al-Sadr, the son of a famous Iraqi Shia theologian executed by Saddam Hussein’s regime, was supported by Iran, which wanted to see US troops removed from Iraq and Shias in charge of the new Iraq.

Al-Sadr’s loyalists were involved in sectarian bloodshed in Iraq that ravaged the country and took thousands of lives after the 2006 bombing of a famous Shia mosque in Samarra by al-Qaeda.

Al-Sadr, however, has gone through a political transformation, concentrating on anti-corruption and leading demonstrations in Baghdad’s Green Zone, where the Iraqi government is ensconced; making alliances with secular Iraqis, including communists; souring on Iran and reaching out to Arab Sunni governments, Saudi Arabia among them.

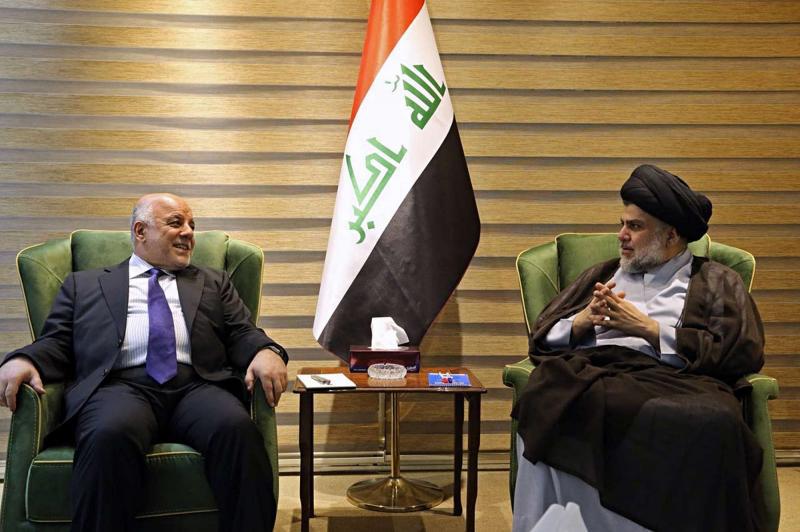

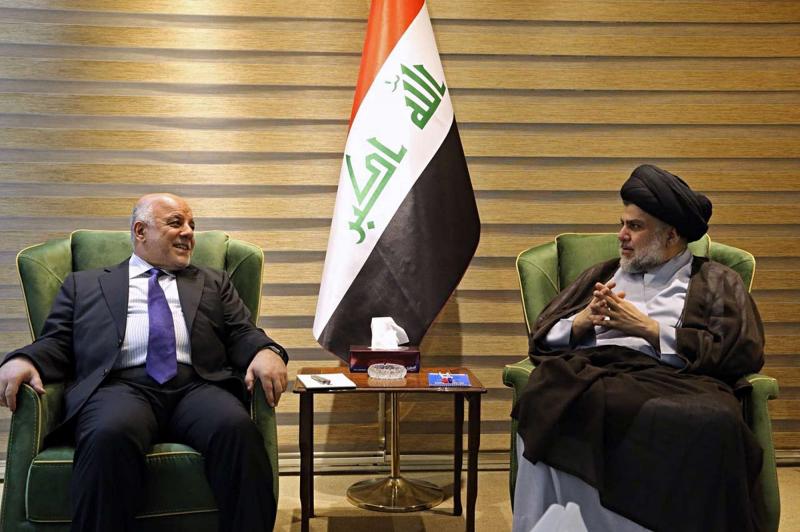

This has proven a clever electoral strategy by suggesting he was an Iraqi nationalist, first and foremost, concerned about the need for clean government and the provision of services. In the recent parliamentary elections, his alliance won 54 seats, followed by Hadi al-Amiri, a leader of the mostly Shia Popular Mobilisation Forces whose Al-Fatih bloc won 47 seats. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s Victory Alliance claimed 42 seats and Vice-President Nuri al-Maliki’s State of Law coalition took 25.

US policymakers were clearly hoping Abadi would win handily because US diplomatic and military personnel developed close ties with him in the fight to defeat the Islamic State (ISIS). Abadi did not seem to object to US forces, which number about 5,200 in the country, staying in Iraq to train the Iraqi Army and ensure that ISIS or like-minded groups would not emerge.

Al-Sadr, on the other hand, has consistently called for all foreign forces, including US troops, to leave Iraq, maintaining that they represent an “occupation” and that Iraq’s security should be in the hands of Iraqis.

The retention of US troops has factored into the Trump administration’s thinking on the results of the Iraqi elections. The US State Department on May 12 issued a statement that congratulated the Iraqi people for having elections that allowed citizens representing all sectarian and ethnic groups to have their voices heard. However, the statement also emphasised the importance of the US-Iraqi partnership based on the Strategic Framework Agreement, which provides for US forces to remain in Iraq.

It is unclear how the post-election wrangling will end up as a new government needs the support of at least 165 parliamentarians out of 329 to function. The United States is hoping that: 1) the Strategic Framework Agreement will continue; and 2) Iranian influence will be minimised to the extent possible.

US policymakers, including those with combat experience in Iraq, have been circumspect so as not to prejudice the government formation. US Defence Secretary James Mattis, whose US Marines fought the Mahdi Army in 2004-05, stated diplomatically: “The Iraqi people had an election… We will wait and see the results, the final results, of the election but we stand with the Iraqi people’s decision.”

Given al-Sadr’s opposition to Iran’s role in Iraq, having his followers in a coalition government may not be all that bad from Washington’s perspective. Iran is clearly upset that the electoral blocs of Amiri and Maliki did not do better in the elections and reportedly sent Major-General Qassem Soleimani, leader of Iran’s al-Quds Force, to Iraq to engage with the Shia politicians to ensure that al-Sadr’s bloc is not part of any ruling coalition.

Should Abadi and al-Sadr form a coalition with Sunni and Kurdish parties, as well as a minor Shia party that is not beholden to Iran, they could conceivably have enough parliamentary support to form a government. The price of retaining al-Sadr’s loyalty, however, may be for Abadi’s bloc to abandon support for the Strategic Framework Agreement.

US military commanders see substantial improvements in the Iraqi Army since the dark year of 2014 when it collapsed in the face of ISIS victories but say the training mission has a way to go. Hence, to leave Iraq prematurely would hinder that mission and put the United States in a position in which it might have to return to Iraq if another extremist group emerges.

It should be remembered that US President Donald Trump, though highly critical of the Iraq war during his presidential campaign, sharply criticised former US President Barack Obama for pulling US troops out of Iraq and leaving a power vacuum that ISIS exploited.

An optimistic scenario from Washington’s perspective would be if Abadi retains the prime minister position, the coalition he assembles remains wary of Iranian influence in Iraq and al-Sadr accepts the Strategic Framework Agreement.

These are a lot of “ifs” for a still-fractured country that has enormous political and economic problems on its plate. It is not clear whether the United States has enough clout to affect the outcome of the government-formation process.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.