Tunisia’s troglodytes follow a different script from Star Wars

MATMATA - Najet sits in her kitchen about 6 metres below ground level. It has no running water nor any of the other basic conveniences much of the world takes for granted but Najet has no plans to leave the 300-year-old house in the southern Tunisian town of Matmata.

“It’s cooler (than above ground),” she says of the mud structure tunnelled deep into the earth. “It’s simple, it’s clean and it has all that’s important for the body when you sleep.”

She means the sound of silence from being underground. Najet was born a troglodyte — one who lives in a cave — except that the Matmatans inhabit mud houses dug out of the earth and carefully constructed to a centuries-old formula.

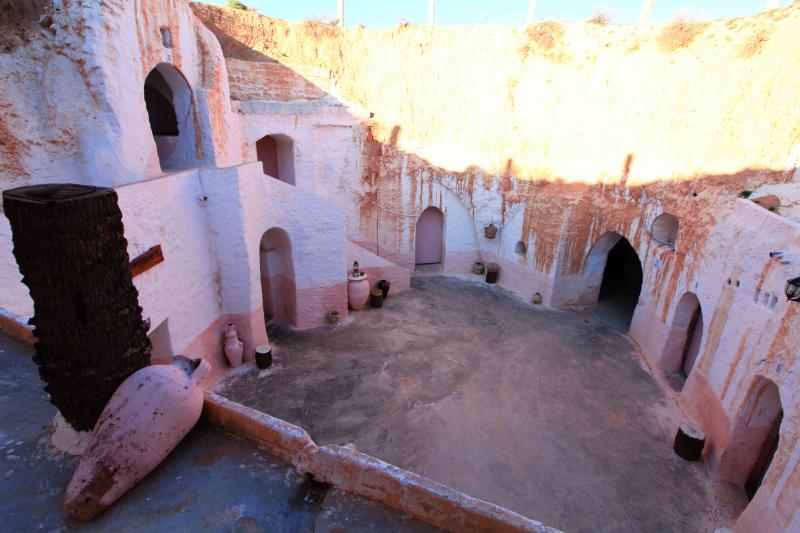

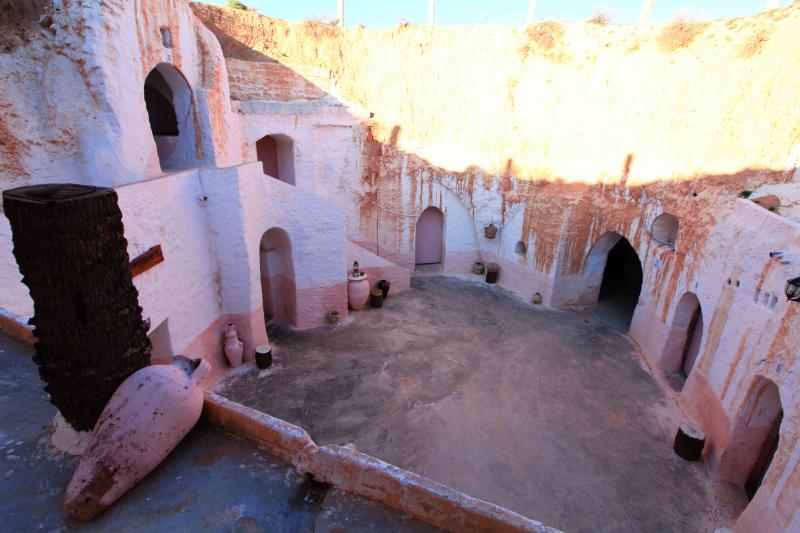

Like those of the approximately 200 Matmatan families who still follow a traditional way of life, the house Najet shares with her husband, Kilani Ben Nasr, and their children has a central courtyard, which resembles a large circular well with vertical walls. It is made of the region’s distinctive clay and gypsum soil. Rooms are built off the courtyard. There is no bathroom or toilet within the structure for fear a leak would seep into the mud and cause the house to collapse.

The vernacular architecture on the edge of the Sahara Desert “melts within its environment,” a paper by British-Egyptian architect Mamdouh Mohamed Sakr states. Matmata, he adds, “has many of the best examples of troglodyte architecture in the world. It is a prime example of a whole settlement of earth-sheltered buildings.”

The settlement is shrinking. In 1967, there were twice as many troglodyte families in Matmata as today. Every year, a few more move to brick houses in Nouvelle Matmata, the new town 15km away. However, many stay on, stubbornly clinging to their unique cultural heritage.

Ahmed Gnouma, 41, is next door to the troglodyte house where he lived from birth until the age of 32. “I always liked how quiet it was underground,” he says wistfully. “I only left because my wife refused to live there. She was used to a modern house and a toilet near the bedroom.”

Khaled Azzouni’s family is trying to marry new ways with old. He lives most of the year in a modern house with his parents, wife and son but returns to the nearby ancestral troglodyte structure every summer. It makes good sense, Azzouni explains: “It’s the same temperature — 27 degrees — all year round even though Matmata in summer goes above 50 degrees. We need no air conditioning in summer or heating in the winter.”

Azzouni’s family is careful to maintain the troglodyte home year-round. “Every week, winter or summer, we clean away the mud that constantly falls. We have a saying in Matmata, a troglodyte house needs the breath of human life to stay alive. If we leave it, it will fall.”

Troglodyte houses may seem an anachronism in the 21st century and they arouse strong emotions — from admiration to prurient curiosity to claustrophobia at the windowless rooms.

In the 19th century, Matmatan troglodytes provoked scholarly interest in the journal of the Royal Geographical Society. It featured Sir Harry H. Johnston’s 1898 account, “A Journey through the Tunisian Sahara,” which admiringly told of Matmatan underground houses so warm and dry in very cold winter weather he thought they were artificially heated.

The troglodyte dwellings became a subject of global fascination after they featured in Hollywood’s “Star Wars” series starting in 1977. In the decades since, Matmata has become a place of pilgrimage for fans of the films. Mostly, they visit Sidi Driss, the rundown underground hotel that was cast as the fictional Tatooine home of “Star Wars” protagonist Luke Skywalker.

Since 2012, Najet has tried to cash in on tourist interest. She opens her house to visitors for a few dinars apiece and sells jars of Matmata’s distinctive rosemary-flavoured honey.

She admits that she is one of a dwindling tribe of true believers in the troglodyte lifestyle. Her married son and two married daughters moved to modern homes years ago. A third daughter, 27-year-old Sabrine, is soon to wed a man who lives in Kebili, the nearest big city.

“I want her to have her own life,” Najet says of Sabrine’s impending departure from the family’s underground home, “but I won’t leave. Later, after my husband and I, this house will belong to our children and I hope they return from time to time. It is their inheritance.”

Azzouni agrees that with every successive generation, the Matmatan way becomes less tenable. “I don’t think my 3-year-old son will want to live in a troglodyte house,” he says. “Young people want technology, the internet… sometimes there are insects like scorpions in troglodyte homes and the young are afraid of them.”

The troglodytes have unlikely additions to their numbers, too. Patrick Bonel left his native France for a 350-year-old abandoned underground house in Tijman village near Matmata. Bonel laboriously restored the house by hand and threw it open as a bed and breakfast, Au Trait d’Union.

“I’ve been here 11 years,” he says, “and I’m not leaving. It’s very good to live underground — 27 degrees maximum in the summer — and very inexpensive besides. You don’t need cement or stone, just hard work to keep it liveable.”

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.