Tunisia balks at inheritance changes

Tunisia celebrates Women’s Day on 13 August, which is also the anniversary of its Personal Status Code (CSP), introduced in 1956 by President Habib Bourguiba (1957-87). This corpus of progressive laws helped to establish gender equality, allowing women to get a divorce more easily and banning forced marriages and polygamy. Thanks to the CSP, which has been improved over the years, Tunisian women enjoy the highest status of any women in the Arab world.

But in the area of inheritance, with a few minor exceptions, they are as badly off as women in other North African countries or the Arab Middle East. The Tunisian legal system, based on Quranic law, specifies that a woman inherits only half as much as a man with the same degree of relatedness. Even Bourguiba, the first president of Tunisia, legitimised by his role in the struggle for independence (he was called the ‘supreme commander’), was unable to challenge this.

Inspired by the writings of the reformist theologian Tahar Haddad (1899-1935), he did manage to ban polygamy on the basis of theological arguments. But the progressive ijtihad (interpretation) he favoured, still criticised today by orthodox thinkers and Islamists, did not extend to inheritance. The Quran is unequivocal: ‘God charges you, concerning your children: to the male the like of the portion of two females. Bourguiba saw this struggle as unequal since we cannot ‘challenge the will of God’. President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011) said in October 1997 that in this area he could not improve on the work of his predecessor.

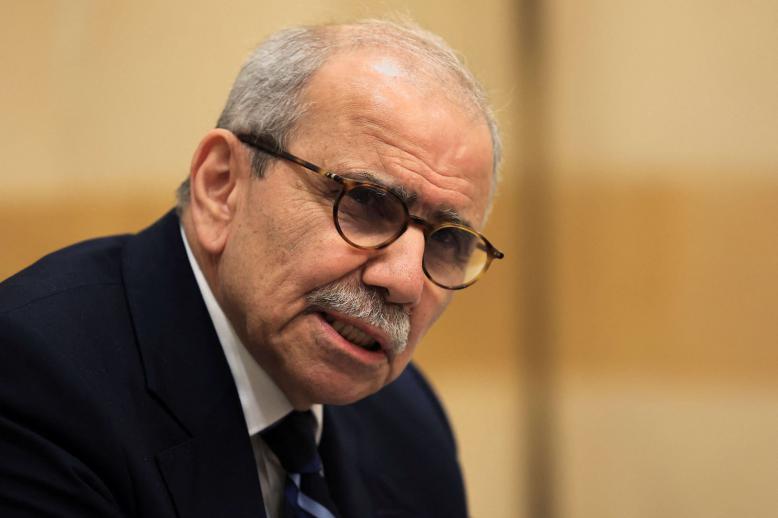

On Women’s Day last year, Tunisia’s current president, Beji Caid Essebsi, put the issue back on the agenda, responding to recommendations by the Commission on Individual Freedoms and Equality (Colibe), which he had established in August 2017. Wisely avoiding demands such as the decriminalisation of homosexuality or the abolition of the death penalty, he agreed to one of the commission’s main recommendations, promising to propose ‘a bill for gender equality in inheritance’.

To justify this decision, Essebsi referred to the 2014 constitution, which affirms that male and female citizens have equal rights and duties. Although the bill was severely criticised by the Islamist party Ennahda, which had declared its opposition to any law ‘contrary to the Quran’, it was adopted by Tunisia’s Council of Ministers in November 2018 and submitted to parliament.

The bill was a first in the Arab world, but not in the wider Muslim world. Turkey freed itself from sharia laws on inheritance in 1923, and Iran’s parliament passed a law similar to the Tunisian bill in 2004, though it was not put into practice because of opposition from the Guardian Council of the Constitution.

Essebsi’s initiative, launched with great fanfare and wide international media coverage, seems to have vanished into the limbo of parliamentary debate. According to a number of MPs, the bill is unlikely to be put to a vote before the parliamentary and presidential elections this autumn. With Tunisia facing a severe economic crisis, a resurgence of terrorist attacks and questions over the health of Essebsi, 92, who suffered a ‘serious health crisis’ on 27 June, the issue of inheritance inequality has been deferred.

This does not surprise Ibtisseme, 31, an unmarried civil servant in Sfax. A year ago, she lost interest in the debates and divisions in Tunisian society over a bill she considers flawed because ‘it allows you to make a will that stipulates a division of your estate according to Quranic law.’ She supports former president Moncef Marzouki (2011-14), and sees Essebsi’s initiative as just a political manoeuvre: ‘Those who claim that the president wanted to complete the emancipatory work of Bourguiba are mistaken. His primary goal was to break the alliance between the prime minister and the Islamists.’ Youssef Chahed, appointed prime minister in August 2016, has gradually freed himself from Essebsi’s influence, even refusing to support the ambitions of Essebsi’s son Hafedh and founding his own party, Tahya Tounes (Long Live Tunisia).

Ibtisseme said there was not much chance of the bill passing. She believes ‘Tunisian society in general hesitates to accept that kind of break with tradition’ and cited her own experience as proof. In 2015 her father, a widower, died and her two brothers inherited more than she did. ‘They didn’t dispossess me in the legal sense. They simply got twice as much, as the law says, including from the sale of the family house and my father’s land. They are both well educated, they are leftwing activists and opposed to the Islamists, but they invoked tradition and refused to have the inheritance divided into three equal shares. Since then I’ve broken off all contact with them.’

There is nothing to prevent male heirs from agreeing, after a parent’s death, on a different division of the inheritance that is fairer to female heirs. They can decide not to follow sharia’s half-share rule, but in practice that rarely happens. As historian Sophie Bessis points out, ‘it’s a matter that touches on two sensitive issues: money and the continuation of the patriarchal order’; the women’s struggle is constantly coming up against these obstacles.

Even before Islam arrived in North Africa, succession favoured men and, in doing so, sought to safeguard the property of the family, clan or tribe. Fatma Bouvet de la Maisonneuve, a Franco-Tunisian psychiatrist, sees the issue as a tangle of taboos: ‘One of them is linked to religion. Clerics and bigots always quote Quranic texts, which nobody dares contradict publicly. They create a way out for themselves by expressing a desire to see them “evolve”, rather than insisting on equality and the primacy of the law.’

Another taboo prevents people from taking steps to ensure that wives, daughters and sisters are not disadvantaged in inheritance: Islam does not forbid making wills or donations, or prohibit couples from opting for joint ownership of assets but, as the Tunisian Chamber of Notaries told me, ‘there are still few people who take steps to prevent difficulties for female beneficiaries’. Bouvet de la Maisonneuve is not surprised, as ‘that would involve talking about inheritance while the parents or spouse are still alive: Tunisians will tell you, “We just don’t do that.” So families who want their daughter to inherit an equal share sometimes make the necessary arrangements in secret.’ Sometimes sons are not aware that their parents have made a notarised donation or equal division, and that can lead to lawsuits. Many Tunisians I spoke to felt such measures were ‘contrary to Islam’.

Women, too, can be resistant to such ideas. A well-known Tunisian intellectual, who wanted to remain anonymous for the sake of ‘conjugal harmony’, told me: ‘My wife doesn’t want me to make an equal donation to my son and my two daughters. She thinks it would be robbing “her” son. She believes the girls will be able to rely on their husbands.’ In September 2017 feminist MP Bochra Belhaj Hmida, who chairs the Colibe, told me how difficult it was to persuade many Tunisian women, including some of the best educated, that Tunisia’s inheritance law needs reforming ‘as a matter of urgency, for the good of society as a whole, and to combat poverty, which affects women more than men.’

Many Tunisians, though strongly in favour of equality in inheritance, insist that such a reform would have severe consequences. When the ulema are asked why such inequality exists, they point out that when Islam first appeared it improved the status of women by allowing them to inherit, which had not always been the case among the peoples of the Arabian peninsula. They claim the half-share rule is justified by the burdens, especially financial, imposed on men by their position in society. New legislation on inheritance needs to be accompanied by an in-depth reform of the status of the head of the family, required by law to ensure that his entire family’s needs are met. Are Tunisian men ready to relinquish this pivotal role, however financially onerous it may be? That would go against the old patriarchal instincts, and not only among Islamists.

Islamists emphasise that sharia can already be used to combat the established traditions of organised dispossession of women. In rural areas, women often do not inherit or are denied the use of land, since all fields are considered to be part of an indivisible property, to be farmed by the men of the family. The women do not always want, or have the means, to take their dispossessors to court. ‘Exheredation’ (dispossession) of women is also found in northern Egypt and Algeria, especially in Kabylia, where custom dictates that women cannot inherit.

In Morocco, the still widespread practice of tasi (banned in Tunisia since 1956) compels women who have no brothers to share their inheritance with other male relatives such as uncles or cousins, though they are not entitled to anything under sharia. Women in Jordan, including Christians, face huge social pressure to give up their inheritance so as not to disadvantage their brothers. In such cases, modernists fighting for gender equality sometimes find unexpected allies among Islamic fundamentalists who demand the strict application of sharia.

Essebsi’s original announcement of the proposed inheritance law sent a shockwave through all of North Africa, including Egypt, where Al-Azhar University felt it necessary to issue a statement that such a reform would constitute a ‘flagrant violation of the precepts of Islam’. Female theologian Asma Lamrabet disagreed, causing controversy in Morocco by taking the position that it was possible to reinterpret the relevant passages of the Quran.

A year on, the enthusiasm has died down and there is no guarantee that Tunisia’s next president will tackle the issue. Even if he does, the final decision will rest with the new parliament. If Tunisia shelves this innovative legislation, it could miss a historic opportunity to relaunch the movement for gender equality in the Arab world.

Akram Belkaïd is a member of Le Monde diplomatique’s editorial team. Translated by Charles Goulden

Copyright ©2019 Le Monde diplomatique - Distributed by Agence Global