Turkey uses virus as opportunity for soft power plays

ISTANBUL - Turkey is pushing its credentials as a major humanitarian power in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic by sending medical equipment to Italy and Spain, detection kits for Palestinians and even medicines to Armenia.

Turkey is hard hit itself by the virus outbreak which has killed nearly 1,300 people but it is still finding the resources to help other countries in need.

Turkey's parliament Tuesday passed a law that will see thousands of prisoners released to curb the spread of coronavirus in the country's overcrowded prisons, but excluded jailed journalists and others awaiting trials on phoney 'terrorism' charges relating to 2016's failed coup attempt, are not included.

In recent weeks, Turkey has supplied masks, hazmat suits and hydroalcoholic gel to Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom, all among the worst hit in Europe.

Turkey's humanitarian aid reflex is not new, Jana Jabbour, a Turkish diplomacy expert at Sciences Po university in Paris, pointed out.

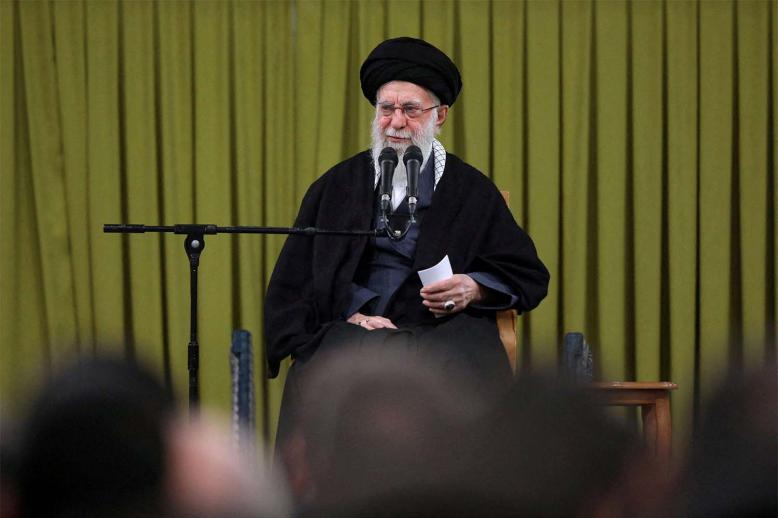

"President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has always wanted to position Turkey has a 'humanitarian power'," quick to rescue those in need, whether they are oppressed Muslim minorities or countries hit by natural disasters, Jabbour said.

But unlike Ankara's usual interventions, Turkey is now also supporting developed countries -- which are more used to helping than being helped.

Prisoners released, but not journalists

The new law, backed by Erdogan's AKP, will allow for the temporary release of 45,000 prisoners in a bid to lighten the load on Turkey's overcrowded prisons and curb the virus' spread within them.

Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gul said on Monday that so far 17 cases have bee detected among prisoners, including three deaths, along with 79 prison personnel and 80 judges and prosecutors.

Opposition members lamented the law for excluding the thousands of journalists and politicians held on 'terrorism' charges following a government crackdown on dissidence in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt.

The number of prisoners has risen to nearly 300,000 since the purge - the second-largest prison population in Europe and the continent's most overcrowded prison system as of January 2019, according to data from the Council of Europe.

It is estimated that 50,000 people that are pending 'terrorism' trials are among the excluded.

Turan Aydogan, from the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), said the law should have been designed to protect freedom of thought.

"You lock up whoever criticises. We tried to find a solution here but you are neutral," he said, addressing AK Party and MHP members in parliament.

Turn the tables

It is also an opportunity to turn the tables for Erdogan, who professes nostalgia for the Ottoman Empire, infamously described as "the sick man of Europe" by Western powers before its collapse at the end of World War I.

"It is a question of showing that Turkey is a strong power which has the means to offer aid to European states, now themselves 'sick', both in the literal and figurative senses," Jabbour said.

To cultivate this idea, each delivery to Europe is carefully staged, from the plane's take-off broadcast live on television to the beneficiaries' warm thanks spread across the newspapers.

Erdogan's spokesman Ibrahim Kalin was quick to point out that "Turkey is the first country in NATO to send help to Spain and Italy," who are also members of the US-led military alliance.

Ties with the West and Europe in particularly have been strained for several years.

The latest spat with the European Union came earlier this year when Erdogan said migrants, fleeing conflict in Syria and across the Middle East, would not be prevented from leaving Turkey for Europe, causing huge numbers to gather on the Turkish-Greek border.

Erdogan insists repeatedly that Europe has not done enough to support EU membership candidate Turkey, which hosts around 3.6 million Syrian refugees.

Relations deteriorated badly as the migrant crisis grew in 2015 and got worse still in 2016 when the EU criticised Erdogan's crackdown after a failed coup.

Erdogan in turn lambasted Brussels for failing to show solidarity with a fellow democratically-elected leader.

"Turkey's candidacy for the European Union is good for Turkey, but it's also good for Europe. In fact, this pandemic has proved us right," Kalin said.

According to Kalin, nearly 100 countries have asked for help from Turkey while Erdogan said on Monday supplies had reached 34 states.

'Strategic angle'

Beyond the PR operation, "there is a strategic angle in terms of the countries that Turkey has picked to send pandemic-related assistance," said Soner Cagaptay, of the Washington Institute of Near East Policy.

When the government last week sent equipment to five Balkan countries, a region once under Ottoman rule, Turkey sought to reinforce its image as a "generous uncle," he said.

Another example is Ankara's decision to send medical equipment to Libya where a civil war between the Turkey-backed government in Tripoli and dissident forces supported by the United Arab Emirates and Egypt have wreaked havoc with the health system.

"Turkey is making sure that the Tripoli government doesn't collapse under the burden of the pandemic. It's part of the wider clash between Turkey and the UAE-Egypt axis," Cagaptay added.

The crisis created by Covid-19 has also offered Turkey an opportunity to extend an olive branch to countries with which it has had frosty relations for many years.

Kalin on Sunday said Erdogan had thus approved the sale of drugs to Armenia.

Despite tensions between the two countries, Turkey agreed to sell medical supplies to Israel, Kalin said, adding that material would also be sent to the Palestinians, for free.