Yemeni women race to sew face masks before virus arrives

SANAA - More than a decade after it closed, 20 Yemeni women have revived the war-torn country's oldest factory to make face masks in anticipation of an outbreak of the new coronavirus.

The situation is especially fraught because Yemen's health system has all but collapsed following years of conflict.

In the factory in the capital Sanaa, rows of desks line a cavernous hall with women in black niqab and white gloves hunched over sewing machines meticulously assembling medical masks.

For them, the situation feels like a race against time to prepare for the kind of outbreak that is already stretching wealthy, stable countries to the limit.

"We have been working on the masks since Monday and, thank God, we started working on them before the disease reaches us as a precautionary measure, without the need to import from outside," mask maker Faten al-Masoudi said.

"I am willing to work here for free for the health of our children, infants and women," added Masoudi who, like all the women, does not receive a regular salary but is paid per mask.

In another section, one women sanitised plastic bags as another filled them with masks.

Yemen, ravaged by an ongoing war described by the United Nations as the world's worst humanitarian crisis, has not yet registered any COVID-19 cases.

Unlike neighbouring Gulf countries, Yemen has not taken drastic measures to prevent the virus' spread, but is also less vulnerable to imported virus cases, with swathes of the country under siege and air links severely curtailed.

The women have nonetheless stepped up to help. Fighting between the Saudi-backed government and the Iran-aligned Huthi rebels has crippled the economy and healthcare system, making their intervention especially timely.

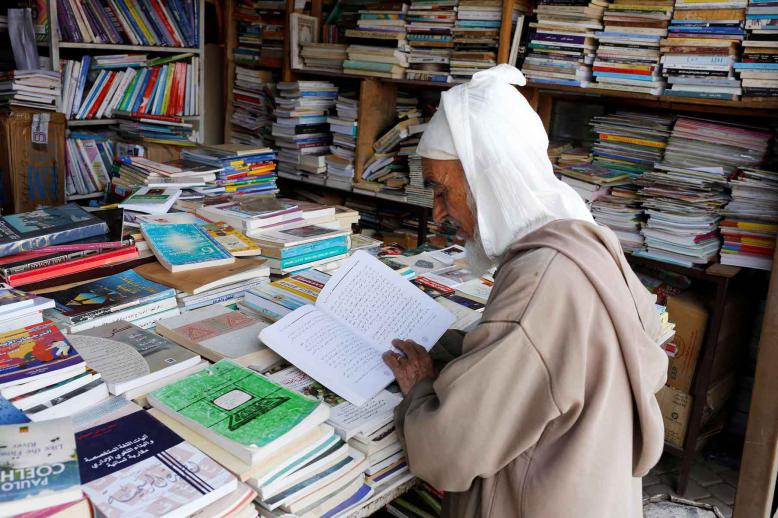

Run-down mill

The storied Chinese-designed factory opened in 1967 producing cotton, which was a major contributor to Yemen's economy in the 1970s, making garments including army uniforms before shuttering in 2005.

Parts of the complex have been damaged in airstrikes while others have become dilapidated.

Abdullah Shaiban, the factory's chairman, hopes the crisis preparations will see the site achieve its "full potential".

"There is a great demand for this kind of mask, which people use to protect their health," he told AFP.

"We transformed a section of the sewing department that manufactures clothes into one that produces masks."

He was hopeful that with 80 machines, the plant could make 8,000 to 10,000 masks daily.

Another factory in Sanaa is now manufacturing hand sanitiser.

'Viruses don't respect borders'

The World Health Organization confirmed Tuesday there were no registered cases in Yemen.

It said it was working with authorities in Sanaa and the southern city of Aden -- where the government has been based after the rebels seized control of the capital in 2014 -- to screen people entering the country.

"The virus does not respect borders," said Yemen's WHO representative Altaf Musani.

"There is a shortfall in the number of tests... we're about to increase... testing capability."

Musani added the WHO had distributed protective kit, including masks and gloves, but not "nearly enough", and was working to get more.

Back at the factory, Shaiban said some opportunistic market traders had hiked imported mask prices to a level unrealistic for ordinary Yemenis.

"This is not something we accept," Shaiban said. "There must be an ethical, moral, religious and humane approach."

Millions are struggling to survive without aid and three million are displaced, many in camps especially vulnerable to diseases like COVID-19.

In Sanaa, the Iran-backed Huthi insurgents who control the capital and large parts of the north have suspended school classes as cases in nearby countries soar.

Nearly 1,000 cases have been recorded across the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations -- mostly among those returning from Iran where nearly 1,000 people have died.

"We have stood firm against war and we will stand firm against this disease," Abdulbasit al-Gharbani, the factory's sewing director, told AFP.

"To beat it, we must stand together."