Yemen's financial crisis hits food imports

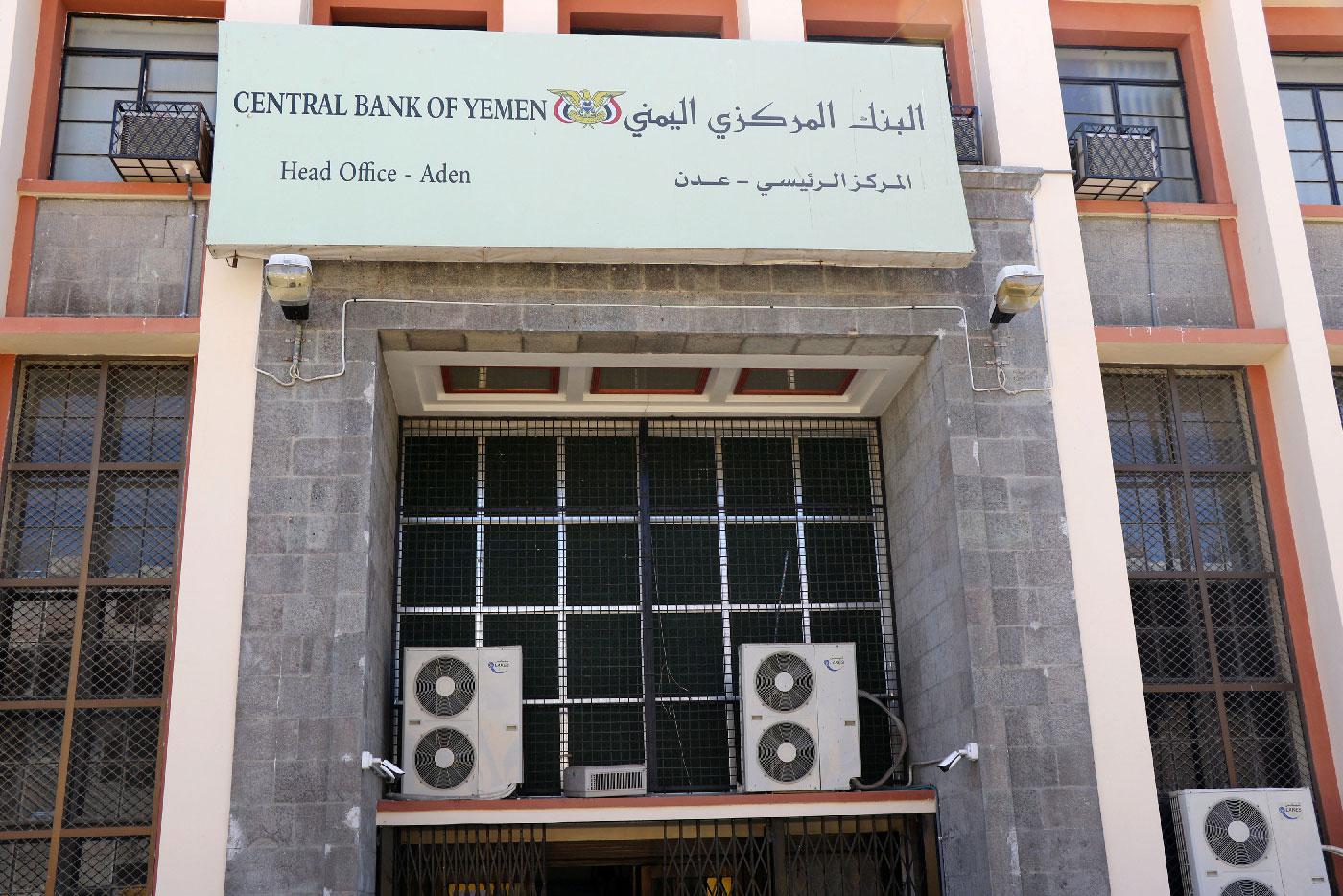

ADEN - The central bank of Yemen, split into two rival head offices reflecting a country divided by war, has been slow to finance imports of food needed to fend off widespread hunger, sources with knowledge of the matter have said.

Saudi Arabia agreed in July to lend $2 billion to the central bank office located in the southern port of Aden, the seat of the Riyadh-backed government, to help finance imports of basic goods.

The loan would enable importers to exchange Yemeni rials for dollars to buy food for a country where a collapse in the currency has left many unable to afford basic foodstuffs.

But an Aden central bank document circulated in November, corroborated by two of the sources, made clear that only a little over $170 million had been authorised for payment.

Deputy Governor Shokeib Hobeishy told reporters last week that the total had risen to $340 million, but it was unclear how much had reached companies wanting to import food.

"There were a lot of regulations that we needed to complete but we have overcome that," he said at his office in the Aden central bank. A sniper perched on a rooftop across the street to provide security.

The rival central bank headquarters in Sanaa, the national capital now controlled by the Houthi group that has been fighting a coalition led by the Saudis for almost four years, did not receive any funds from the Saudi loan.

That was to be expected, given the realities of the war. But with the Saudi loan going to Aden, money has been directed away from Houthi-controlled areas in the north where most food imports arrive.

Traders who previously did business through the central bank in Sanaa are now scrambling to work through Aden, a switch that has created more hold-ups and payment problems.

Difficulties

A senior official at the Aden central bank, who declined to be named, said the bank was having difficulties.

"There is confusion at the central bank level ... no one has a clue about the whole landscape," the official said. "This is happening because there is no senior leadership or oversight."

Some traders say the Aden office favours government-held areas. Hobeishy denied that, saying there was no question of his bank issuing letters of credit to those doing business in some areas of the country and not others.

He also cast doubt on the status of the central bank in Sanaa. "There is no such thing as two central banks in Yemen, there has always been just one bank and we moved to Aden," he said.

The government moved the central bank to Aden in 2016, accusing the Houthis of squandering $4 billion of bank reserves on the conflict. The Houthis say the funds were used to finance food and medicine imports. A Houthi spokesman had no immediate comment for this article.

The top official at the Sanaa central bank, Mohammed al-Sayani, said that a regulation issued by the Aden bank in June made it costly and almost impossible for food traders based in Sanaa to benefit from the Saudi loan.

The regulation means traders must get letters of credit in Aden and ensure their goods arrive there, he said.

"Around 80 percent of these food traders are based in Sanaa," he said. "This is biased and it is a kind of an economic war for political ends. They have all their infrastructure, like silos etc, at the ports in Hodeidah and Salif."

Truce brings hope

In a move that could make it easier to bring in food, the two sides agreed at United Nations peace talks last week on a truce and troop withdrawal from the Houthi-held port of Hodeidah.

Opening Hodeidah was a vital starting point to get imports flowing, a UN official said.

"Then we need to solve the other problems like access, in particular, to currency from the central bank," said Abdessalam Ould Ahmed, the FAO's Assistant Director-General and Regional Representative for Near East and North Africa.

Hodeidah handles 70 percent of Yemen's imports of commercial goods and aid. It is a lifeline for 15.9 million people facing severe hunger in the impoverished nation of 30 million.

The World Food Programme said the truce should allow access to 51,000 tonnes of its wheat stocks cut off since September due to fighting.

One big importer, who declined to be named, said it was not possible to ship new wheat cargoes to Hodeidah and Salif due to lack of payment. The importer was still waiting for over $50 million in foreign currency.

A second grain importer had yet to receive about $20 million in foreign currency and had stopped new shipments.

"Private traders have to pay for the goods before they are even shipped out, so they are already out of pocket," the second trade source said.

Reserves dwindle

The United Nations said Yemen needs billions of dollars in external support to avoid another currency collapse.

The central bank is struggling to pay public-sector wages as foreign exchange reserves dwindle. It has access to a Federal Reserve account of $200 million while around 87 million pounds are frozen in a Bank of England account. The Bank of England declined to comment.

Authorities sought to boost liquidity last year by printing money. Since then the rial has halved in value.

The United Nations and the International Monetary Fund are working to reunite the rival central banks.

The chairman of Yemen's Gulf of Aden Ports, Mohammed Alawi Amzerbah, said around 85 percent of goods arriving in Aden can make it to Houthi-held areas. But a day later, a celebration at a location two hours from Aden to launch a road to transport goods northwards was cancelled for security reasons.

Yemen's problems go further than importing food. In Aden's fish market onlookers cheered as a fisherman displayed his catch, a small shark, but customers were scarce.

"Before, you could buy that shark for 2,000 rials. Now you need 7,000 rials," said Nasser Bureik Nasser, a fisheries ministry employee.