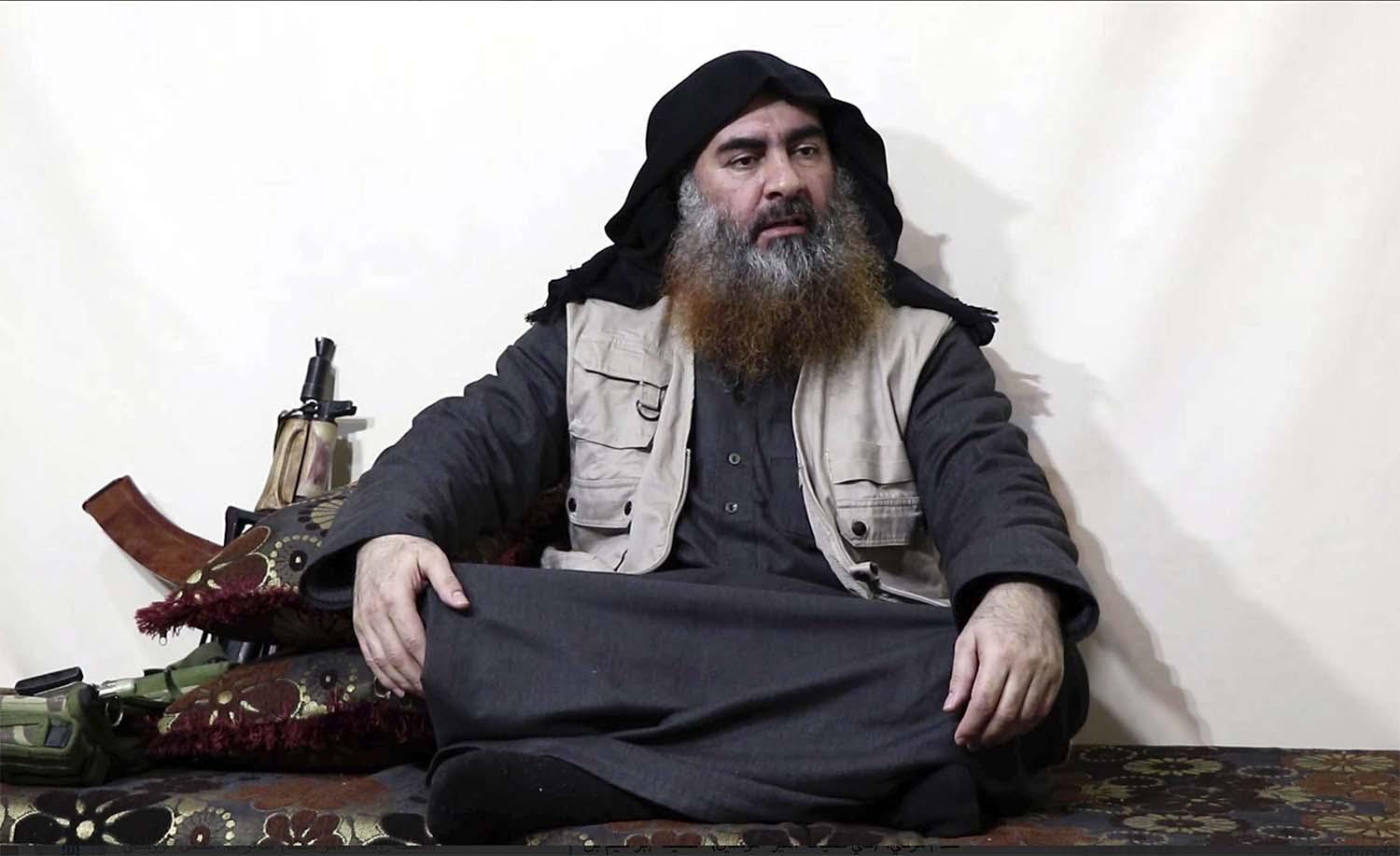

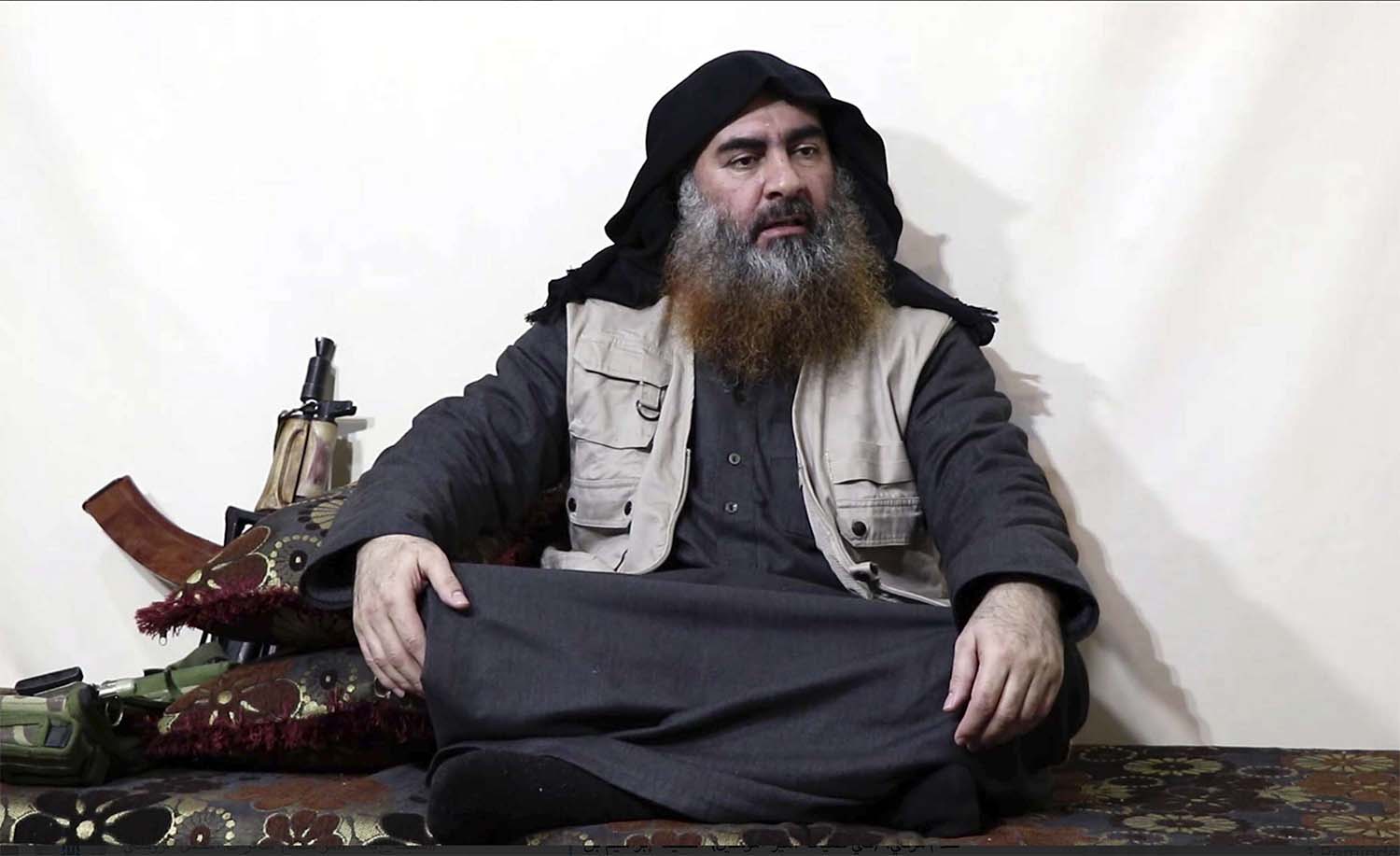

The Death of Al Baghdadi won’t end the violence but it will change the Jihadi landscape of the Middle East

After the leader dies, the followers regroup. The killing of Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi has ushered in days, and possibly weeks, of media and political wrangling over the true story of the raid that killed him, and who ought to take credit for finally catching one of the world’s most wanted men. But away from the cameras, a reorientation will be taking place.

ISIL still has thousands of fighters in the Middle East – the UN last year estimated perhaps 18,000. Many are in sleeper cells or operating semi-autonomously. Hundreds more are thought to have escaped from Kurdish prisons when Turkish troops swept across northeastern Syria in October. That is to say nothing of the groups from West Africa to the Philippines that have pledged allegiance to the terrorist organization. The death of Al Baghdadi changes none of that.

Instead, what his death does is to create an opening for changes in the jihadi landscape in the Middle East. It opens up the possibility of reconciliation between previously antagonistic groups, the emergence of new leaders and the rise of a new jihadi threat. Far from bringing an end to the bloodshed of jihadism, the death of Al Baghdadi merely closes one chapter.

In many way, jihadi groups function in much the same way as political parties. Successful groups attract followers and money. A compelling story, a charismatic leader, a sense of momentum: all of this can shape how a jihadi group is seen and bring in more support.

ISIL, with its attempt to establish a “caliphate,” had an enormously powerful story, one so potent it dragged tens of thousands of young men and women to the proto-state from their homes and jobs in cities and towns across Europe, the Middle East and Asia. But as the territory it controlled finally was chipped away, first in Iraq and then in Syria, its followers drifted from the central leadership, focusing on local issues and self-funding.

With the death of Al Baghdadi, these groups need a new leader and direction. The only real question is where this will come from. It could emerge from a new leader within ISIL’s current leadership structure, or from those fighters swelling the ranks of another existing group.

Indeed, a resurgence after the death of a leader is exactly what happened to ISIL itself a decade ago. After the Jordanian militant, Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, who founded it was killed in 2006, the group, then called Al Qaeda in Iraq, merged with other militant groups, acquired a new leader and moved away from the international fight that Al Qaeda was waging toward, instead, a domestic one in Iraq.

When Al Baghdadi took over the organization four years later, he pivoted back toward an international focus, drawing in foreign fighters. But he kept one crucial idea that had been formed in the years after Al Zarqawi’s death: a caliphate inside Iraqi and Syrian territory. Within a few years, after the Syrian civil war broke apart that state, the organization and the idea found its moment.

Whatever group or iteration comes along next will learn from the ISIL that was. In exactly the same way that political groups learn from others around the world, jihadi groups will look to what came before and seek to replicate the successful elements. For Al Baghdadi’s ISIL, those elements were a powerful story: the weaponization of cruelty caught on camera to terrify opponents and inspire a global audience, and the importance of controlling towns and cities to generate funds and provide work for the population the group moves among.

It is noteworthy that Hayat Tahrir Al Sham (HTS), the former Al Qaeda affiliate that is now the largest militant group in Idlib, Syria, already does generate funds and provide jobs. If any group in the Middle East is well-positioned to sweep up ISIL fighters and be the most immediate beneficiary of Al Baghdadi's death, it is HTS.

Although HTS and ISIL were rivals, with Al Baghdadi dead there is an opening for a reconciliation and the merging of some groups. HTS has shown itself to be more pragmatic than ISIL, forging alliances among the various competing militant groups inside Idlib. However, HTS’s goals, for now, are focused on Idlib, which may alienate those who believe in ISIL’s global ambitions.

Whether HTS benefits from Al Baghdadi's death will turn on several factors, some internal to jihadism, such as the question of whether to wage global jihad or build a small state, and some external, for example, whether the Assad regime or Turkey overruns Idlib.

But what ISIL proves is that success brings recruits. With Al Baghdadi dead and ISIL’s fighters scattered, HTS is the most coherently-led and best armed group across Syria and Iraq espousing jihad. It is in the best position to draw in new recruits and take them in a new direction.

What Al Baghdadi’s death will not do is stem the violence.

Jihadism is a response to political issues that exist around the world, and still exist in the Middle East. The destruction of previously functioning states – in Iraq by the 2003 invasion, in Syria by the civil war – may have created opportunities for jihadis, but the underlying tensions they exploited of a lack of employment opportunity and poor governance were already there. That remains the case in other areas that have sent fighters to ISIL, whether from deprived areas of Europe or Asia. The root causes are political.

Until those aspects are dealt with, the death of any particular figure – even one so shrouded in mythology as Al Baghdadi – means more for those in front of the cameras than for those on the ground.

Faisal Al Yafai is currently writing a book on the Middle East and is a frequent commentator on international TV news networks. He has worked for news outlets such as The Guardian and the BBC, and reported on the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa.

Copyright: Syndication Bureau