Don’t just impose sanctions on Turkey – make sure they’re ‘smart’

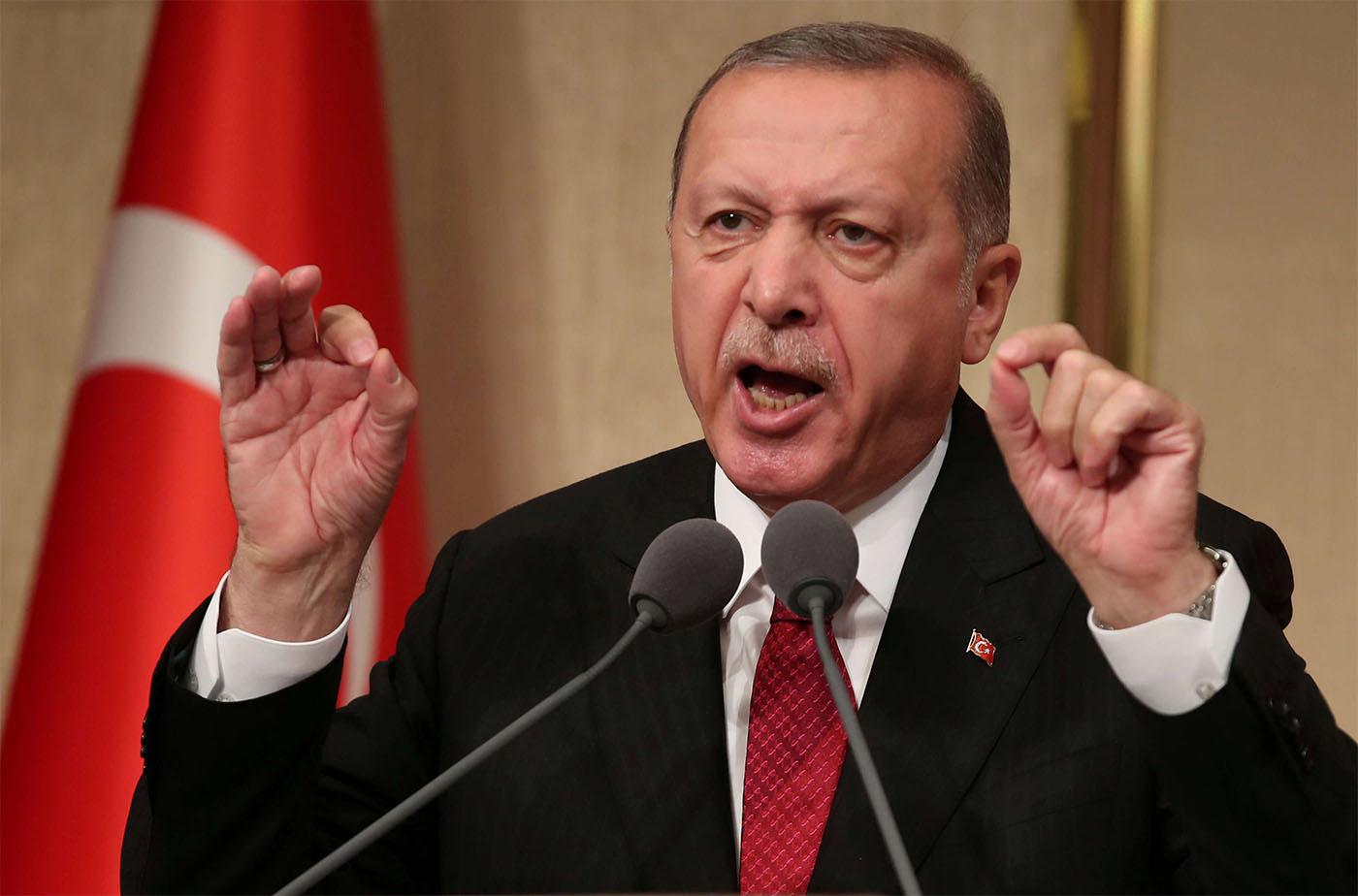

Given the constant turbulence in Turkish-American relations, Washington’s national security establishment no longer considers Ankara an ally. Instead, it perceives Turkey to have moved resolutely into Moscow’s orbit. Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent agreement with Vladimir Putin to establish a safe zone along almost the entire 400-kilometer-long Turkish-Syrian border – to be patrolled by Russian military police and Turkish soldiers – only confirms this in their mind.

The agreement is a net win for Russia and the Assad regime, and a net loss for Washington and its Kurdish allies. Thus, there now is bipartisan support in Congress for fresh sanctions against Turkey – following the abandonment of the last set of punitive measures. Anti-Turkish sentiment is mounting not only due to Erdogan’s invasion and reports of war crimes, but also because of Ankara’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 missile-defense system. Many Republican legislators who defend Donald Trump against the Ukraine impeachment inquiry are itching to punish Turkey, if only to show they are not blindly following the White House.

Although some caution that renewed sanctions will only push Turkey further into Russia’s embrace, most US legislators believe Turkey already is well and truly there. Thus, they have no compunction about ramping up sanctions and dialing up the hurt. Indeed, there is widespread agreement in Washington circles that the only language Erdogan understands is coercive diplomacy backed by a big stick. On the House and Senate floor, then, this will translate into a veto-proof two-thirds majority in favor of CAATSA – the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act – which will target Turkey’s financial and military sectors. But America’s legislators should be careful.

Once implemented, the sanctions that most legislators believe to be both justified and necessary will badly hurt the Turkish economy and the majority of the population. A free fall of the Turkish currency, the lira, will cause more inflation, more bankruptcies and certainly more unemployment.

Erdogan is likely to exploit the worsening economic conditions by resorting to Turkish nationalism and anti-Americanism. He will seek to turn it to his domestic advantage. And in so far as this is expected, sanctions against Turkey – at least as they are currently envisaged – will have a distinctly negative effect on American interests.

So, the question is this: is there a way to hurt the Erdogan regime without hurting the Turkish people? (And America’s own interest.) The late 20th century was littered with sanctions that failed to achieve anything positive. But there is now a wide array of literature on how “smart” sanctions can target specific sectors and officials, rather than society at large – and in so doing, deliver pain where it is more likely to effect the desired policy change.

America already understands this, in fact. On October 14, shortly after Turkey’s incursion into Syria, the US Treasury took just such measures. It blocked the Turkish ministries of defense and energy from accessing the US financial system. The designation of these two Turkish entities, and their senior officials, effectively cut them off from any transactions involving the US dollar. But in his “unparalleled and great wisdom,” Donald Trump lifted those surgical measures in recognition of the Erdogan-Putin agreement on the northern Syrian safe zone. (So much for great wisdom.)

This week, Congress will debate imposing its own sanctions. But as it discusses ways and means to punish Turkey, legislators should keep in mind the Treasury’s selective tactics. They must have very clear ideas about what the sanctions are meant to achieve. This means that the sanctions must be as sharply targeted as possible on specific military and financial areas.

So instead of broad and indeterminate goals, they should be clearly linked to specific demands the US makes against Turkey. In that respect and in the current circumstance, Turkey should be asked to: commit to not activating the Russian S-400 missile-defense system; commit to ensure no ethnic cleansing takes place in Syria by its military and proxy Arab forces; and commit to ensure no war crime is perpetrated under its watch.

These clear red lines should be coupled with face-saving incentives for Erdogan to change course. Again, specifically and in the current circumstance, Turkish compliance should be tied to Ankara’s return to the F-35 stealth fighter-jet program, financial aid for the purchase of the American Patriot missile-defense system and a pathway for a free-trade agreement between Turkey and the United States.

Coercive diplomacy often is the art of finding the right balance between sticks and carrots – a policy of all sticks and no carrots is guaranteed to fail. Thus, ultimately, Erdogan should be made to feel pressure for his actions, but also be allowed to see he has options and room to manoeuvre.

Omer Taspinar is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor of national-security strategy at the National Defense University in Washington.

Copyright: Syndication Bureau