Egypt’s Nubians hold on to ‘right of return’

CAIRO - Nubian activists vowed to fight to obtain the right of return to their historical villages in southern Egypt after the government said it would compensate those forced to leave the villages.

“The government just wants the Nubians to drop their right to return to their original villages,” said Nubian activist Hani Youssef. “This is totally unacceptable.”

The government has started unprecedented measures to compensate Nubians forced to leave homes in southern Egypt because of construction of the Aswan Reservoir at the beginning of the 20th century and the High Dam in the 1960s.

A government committee studied compensation requests from residents of historical Nubia, which included the southern part of Egypt to the border with Sudan, or their heirs.

The committee said it expects more than 11,000 compensation requests, Parliamentary Affairs Minister Ashraf Marwan said.

He said Nubians who had lost land or flats would be given plots in other areas, including in Cairo, the city of Aswan and in the northern coastal city of Alexandria.

The compensation is a revolutionary move by the administration of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who pledged in his election campaign in 2014 to help Nubians displaced by development projects.

“This is a great move, even as some of the residents of historical Nubia are not satisfied with the compensation offered by the government,” said Yassin Abdel Sabour, a member of parliament from Nubia.

Dozens of Nubian villages were threatened by Nile flooding. The Aswan Reservoir and the High Dam were designed to control flood water and protect thousands of villages in the Nile Valley and Delta.

The projects created devastation of another type, however, affecting historical Nubia, its distinct culture, way of life and language.

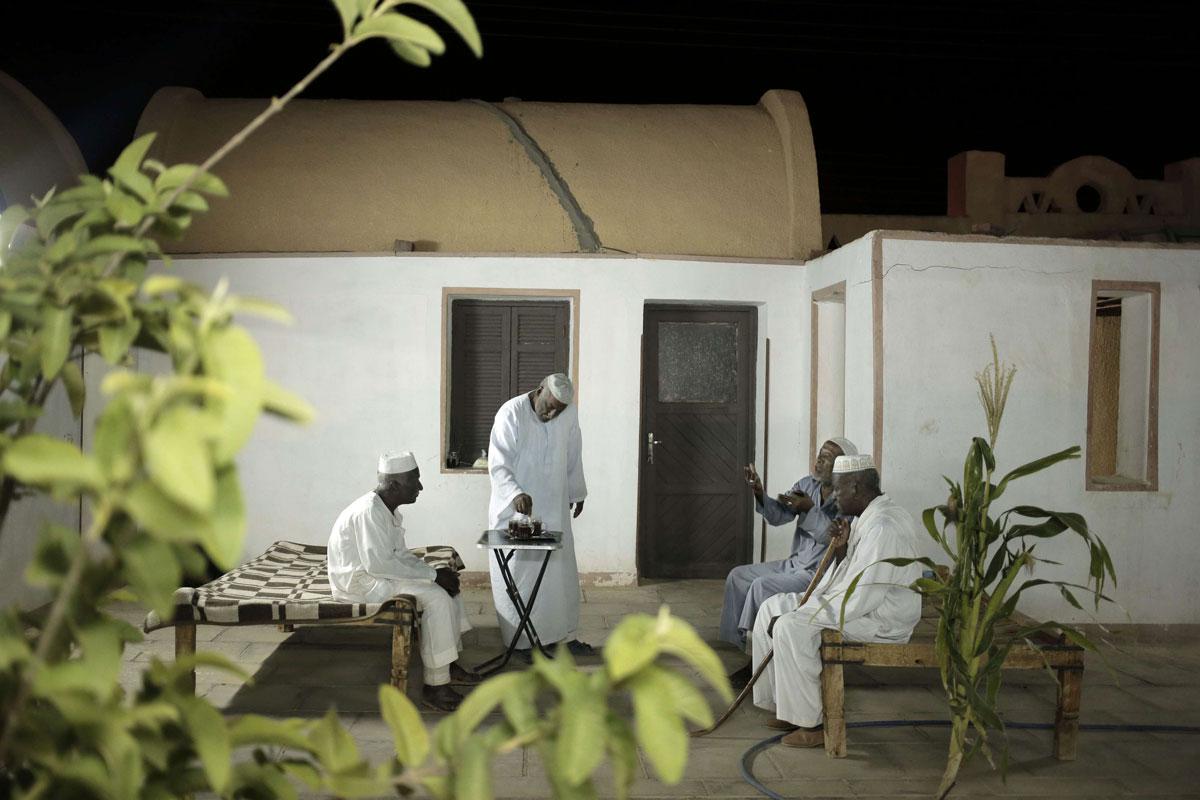

Most of the Nubians moved north into other cities. They call themselves “Nubians in the Diaspora.” When they moved to other places, the Nubians tried to mimic the way of life of local residents.

That meant the Nubian language, which has its own alphabet and vocabulary, began to disappear while Nubian traditional dress and cuisine also were affected. Few Nubians who lived in historical Nubia are alive.

“This was a great loss, not only for the Nubians but also for humanity at large,” said Mustafa Abdel Qadir, a Nubian culture specialist. “Geography and the times were far stronger than the ability of the Nubians to hold onto their own culture.”

Nubian elders refused to speak Arabic, even after they migrated to other parts of Egypt. Some of them passed the Nubian language to their children and grandchildren but this was far from enough to preserve the Nubian culture.

This is probably why rights groups started a campaign against the plan of the government to compensate the Nubians for the loss of their homes and farms. The compensation, the groups said in a statement, should not do away with the right of Nubians to return to villages in historical Nubia.

“The compensation is, in effect, an attempt to get around the right of the Nubians to return to their original villages,” the statement said.

They said giving the Nubians flats and plots of land away from historical Nubia would devastate the Nubian social fabric and destroy Nubian identity, culture and language.

The groups added that financial compensation for the Nubians and denying them the right of return violates the Egyptian constitution.

Article 236 of the 2014 constitution stipulates that the authorities must implement projects to develop the original areas of the Nubians and allow them to return to them within 10 years.

This is why Youssef and other activists call for enforcing the constitution as far as Nubia is concerned.

“The Nubians only want to return to their original places and the land of their ancestors,” Youssef said. “This is a right they will never give up, regardless of any talk of compensation.”

Ahmed Megahid is an Egyptian reporter based in Cairo.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.