Erdogan’s gunboat politics is dangerous

A s the United States takes a backseat in the politics and policies of the Middle East it leaves behind a vacuum of influence, upsetting the status quo established since the end of World War II.

Competing for that political void in the Middle East are:

1) Russia, which, as part of the Soviet Union, was the only other superpower to seriously represent a threat to the United States; then no US administration would dare ignore the tumultuous Middle East, as is the case today.

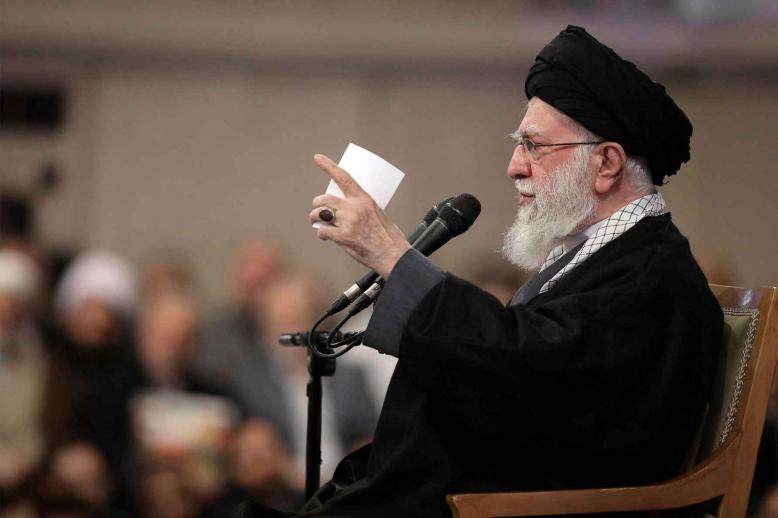

2) Iran, which historically saw itself as policeman of the Middle East and continues to act as though it can fulfil that role, except that its sectarian agenda is a turn-off for most of the Arab world.

However, since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 overthrew the monarchy and established an Islamic republic, Tehran has become the regional exporter of terrorism by proxy. It has tried to appear to wave the flag of Islamic radicalism, promising the defeat of the United States and the utter destruction of Israel, but it has been discredited by its blatant impotence in the face of both countries, except from its occasional burning US and Israeli flags.

3) Turkey — also non-Arab — under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who is driven by neo-Ottoman expansionist visions of grandeur, where he sees himself as the great sultan of all times.

Hoping — or rather fantasising — Turkey is the new regional superpower; as the gendarme of the Middle East and North Africa, Erdogan wants to flex Turkish muscle all over the map.

Erdogan’s Turkey envisions a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to revive its old empire with the support of Islamist soulmates across the Middle East. Having been refused membership in the European Union, the Turkish leader turned eastward.

Clearly, Erdogan’s Turkey is overreaching, as illustrated by his announcement of a second military base in Qatar (after his bases in the Horn of Africa) and his expressed readiness to send troops to Libya, a country in the middle of civil war. He is projecting military power in all directions and that is likely to spread too thin before he knows it.

Already, he has intervened militarily in Syria, hoping to create new realities in that country, where his Kurdish nemeses simply do not exist.

All this points to a single conclusion: Erdogan’s ambition to exert wider influence in the region through military means. He aspires to become the gendarme of the Mediterranean and North Africa, a region that has had enough of foreign gendarmes, self-appointed sentries and mercenary warlords.

Erdogan is living in a militarised dreamworld, some might say on a nightmarish planet, where he is trying to bite off far more than he can chew.

Under Erdogan, Turkey seems to be drifting dangerously, along a path drawn by a leader who sees his dreams as achievable at the barrel of the gun.

Relations with the United States are not at their best and now the sultan is threatening to expel the United States from the Turkish base at Incirlik. That kind of threat plays well with his Islamist crowds, even if in private meetings he is likely to be accommodating to a transactional US President Donald Trump.

Erdogan is angry at the West for daring to censure him. Like most authoritarian rulers he cannot stand criticism. During the past few weeks, he probably found it hard to restrain his vindictive urges against the West for being rebuffed at the NATO summit in London where his self-serving definition of terrorism was widely rejected. Continued anti-American populism might be expedient for him at home but will further alienate Turkey from NATO and the United States.

Erdogan is starting to posture like the head of a superpower, which he obviously is not. His brand of gunboat diplomacy is dangerous for the region and for Turkey itself.

Claude Salhani is a regular columnist for The Arab Weekly.

This article was originally published in The Arab Weekly.