Iraq parliament speaker battle exposes deep Sunni divisions

BAGHDAD –

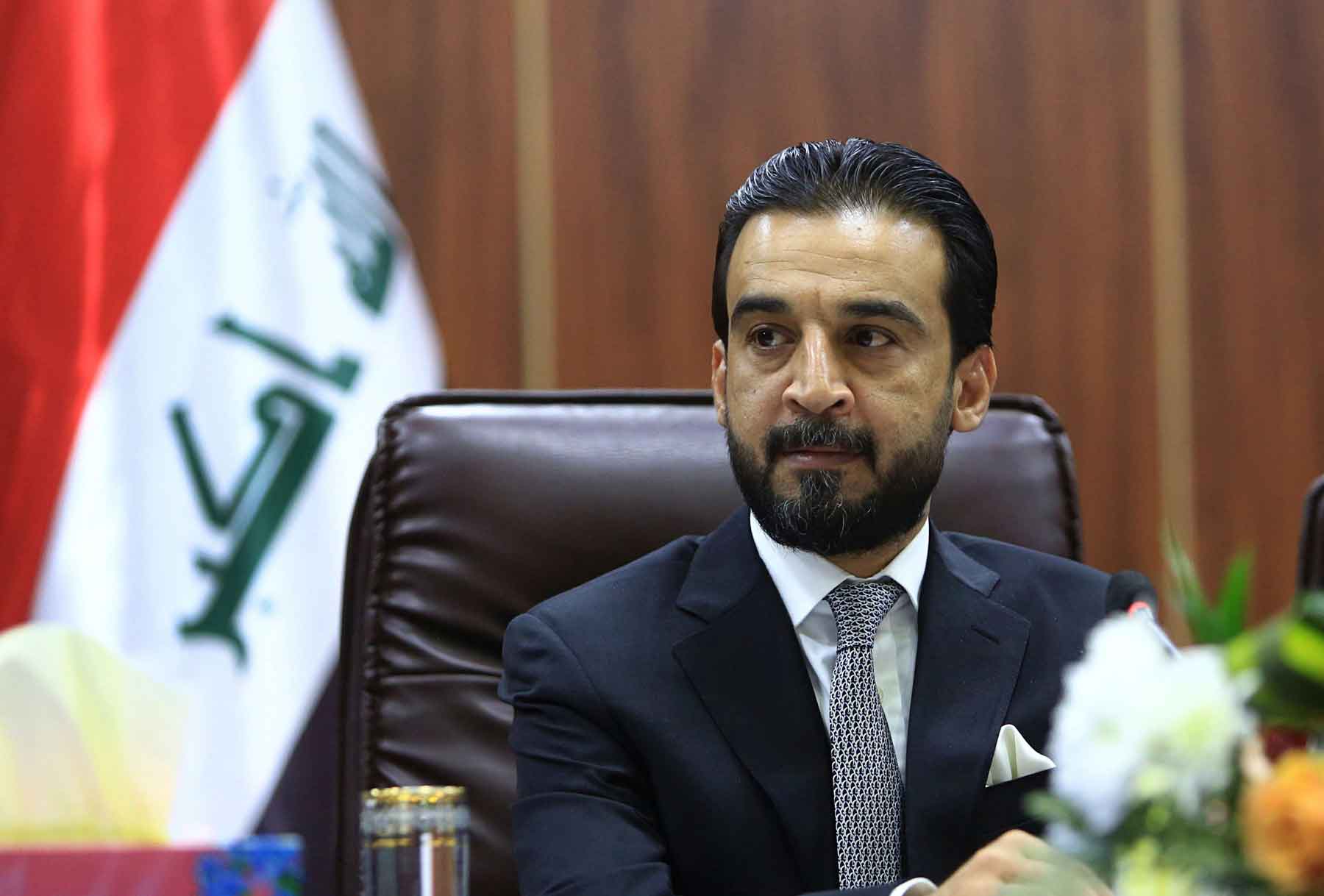

A strong showing at the ballot box has not been enough to secure Mohammed al-Halbousi’s return to one of Iraq’s most powerful posts, underscoring the fragility of Sunni political unity as the country moves to form its next parliament and government.

Halbousi, a prominent Sunni politician, saw his Taqaddum party win 27 seats in parliamentary elections held last November, a result that would normally position him as a frontrunner to reclaim the speakership, a post customarily allocated to the Sunni component. Yet his prospects remain uncertain, weighed down by deep rivalries within Sunni ranks and resistance from Shia and Kurdish power brokers whose backing is essential for securing the role.

Halbousi previously served as speaker following the 2021 elections before being removed by a court ruling in a case driven by political rivals, both from within the Sunni political establishment and beyond it. That episode continues to shape the current contest, leaving his candidacy exposed to vetoes from opponents motivated by sectarian, ideological and economic considerations.

At the heart of the struggle lies competition within Sunni politics itself. Chief among Halbousi’s rivals is Muthanna al-Samarrai, leader of the Azm alliance, who is widely regarded as both a political adversary and a direct competitor for influence across Sunni-majority provinces. Although both figures belong to a newly formed Sunni political council created after the elections, their partnership is seen as tactical and temporary, aimed at maximising Sunni leverage in the distribution of power rather than resolving long-standing rivalries.

The council recently held a meeting to explore scenarios for selecting a candidate for speaker. According to a source cited by Shafaq News, one option under discussion is to nominate two candidates, Halbousi and Samarrai, and hold an internal vote next week, ahead of the first session of the new parliament. Iraqi President Abdul Latif Rashid has set December 29 as the date for that inaugural sitting of parliament’s sixth term.

The same source said Samarrai currently enjoys stronger chances of securing the speakership. If he prevails, Halbousi’s camp would reportedly be compensated through control of key ministerial portfolios in the next government, including the defence ministry, a familiar formula in Iraq’s power-sharing system.

However, the calculations extend beyond Sunni politics. The Sunni council has received signals from Shia and Kurdish parties rejecting Halbousi’s return as speaker, while indicating possible acceptance of him as a vice president or deputy prime minister, provided those posts are not scrapped as part of cost-cutting measures under discussion.

Time pressure is tightening the noose. Iraq’s dominant Shia forces, which continue to lead the governing process, have shown unusual insistence since the elections on adhering to constitutional timelines, driven by internal, regional and international pressures that could affect the country’s stability if prolonged political paralysis returns.

Under Iraq’s constitution, the president must convene parliament within 15 days of ratifying election results to elect a speaker and deputies, followed by the election of a president within 30 days and the nomination of a prime minister to form a government.

Behind the scenes, regional influence is also at play. Observers say efforts by Sunni parties to agree on power-sharing arrangements have been subject to intervention by regional states seeking to elevate allies and secure footholds of influence in Iraq. In previous months, reports circulated of Turkish and Qatari mediation aimed at narrowing differences between rival Sunni leaders and bringing them under the umbrella of the new council.

Formally named the National Political Council to avoid overt sectarian labelling, the body reflects the enduring reality of Iraq’s quota-based political system. It emerged from an electoral map that pushed some of the fiercest Sunni rivals into a single framework, mirroring, albeit on a smaller and weaker scale, the Shia Coordination Framework that dominates Iraqi politics.

Sunni parties hold no more than 77 seats in the 329-member parliament, a numerical weakness that has reinforced the incentive to unite. Yet that unity remains fragile. Despite respectable electoral results for several Sunni factions, their seats risk losing influence if fragmented and overshadowed by larger blocs.

Preserving the Sunni share of power was the primary driver behind the council’s creation, but it has not eliminated intra-Sunni competition. On the contrary, many analysts expect internal disputes over posts and privileges to resurface quickly, potentially leading to the council’s collapse, a fate that befell several previous Sunni alliances, including ones formed by the same leaders now seeking unity.

Ironically, the council brings together figures who previously cooperated with Shia parties to remove Halbousi from the speakership and even sought to sideline him entirely through legal cases designed to end his political career.

As Iraq approaches the constitutional deadlines for forming its next parliament and government, the battle for the speakership has become a test not only of Halbousi’s political survival, but of whether Sunni leaders can translate electoral gains into durable influence within a system still dominated by rival blocs and external pressures.