Pakistan eyes strategic pivot in Middle East amid domestic pressures

Over the past several years, particularly since the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in 2021, Pakistan has come under mounting pressure. Persistent terrorism, economic fragility, and diplomatic marginalisation have collectively strained the state’s capacity and strategic confidence. Yet the Middle East and North Africa’s rapidly evolving political and security landscape has opened an unexpected window of opportunity. Within Pakistan’s establishment, there is now a growing view that this shifting regional environment offers not only a way to manage immediate pressures, but also an opportunity to recalibrate Pakistan’s strategic role and external identity.

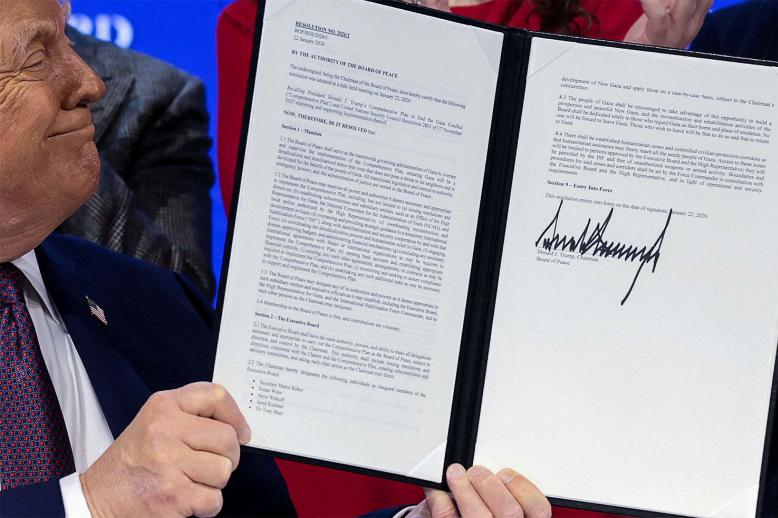

The recent defence agreement with Saudi Arabia marks a turning point. Islamabad is actively encouraging other Arab states to explore similar arrangements. In early November, Pakistan’s president offered Qatar’s emir an expansion of bilateral cooperation in defence production. The defence minister has also repeatedly signalled Pakistan’s openness to participating in a proposed Gaza International Stabilisation Force, while explicitly ruling out any role in the disarmament of Hamas.

These initiatives have coincided with an uptick in high-level military diplomacy. Army Chief General Asim Munir has visited Egypt, Jordan and most recently Libya, where an arms sales agreement reportedly valued at up to $4 billion was concluded, alongside reciprocal visits to Islamabad by Jordan’s King Abdullah II and the Saudi army chief.

Parallel to this external outreach, Islamabad adopted the 27th constitutional amendment on November 12, expanding the military’s institutional authority. This recalibration of Pakistan’s internal power structure reflects not only domestic political realignments but also shifting regional priorities, within which the Middle East has assumed increasing strategic centrality.

Pakistan’s expanding role in the Middle East is underpinned by three key benefits and strategic drivers, yet the country also confronts two critical challenges and vulnerabilities.

Benefits and strategic drivers

Pakistan’s expanding role in the Middle East benefits the state as a whole, but it also yields separate and significant institutional gains for the military. External defence partnerships reinforce the military’s position within Pakistan’s domestic power structure. In a state grappling with economic fragility and heavily reliant on Gulf partners for financial support, the military’s autonomous policy role in these same states further strengthens its leverage at home.

Until few months ago, the armed forces were under intense internal pressure. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) placed the military squarely in its political crosshairs, while sustained social media campaigns visibly damaged its public image. The four-day military confrontation with India in May, widely viewed domestically as a competent operational performance, followed by the Saudi defence agreement and emerging Middle Eastern opportunities, has contributed to the restoration of confidence within the military.

Across much of Pakistan’s political spectrum, there is now a growing acceptance that accommodating the military’s role within the political system offers a more viable path toward stability and continuity of governance. This hybrid political order appears acceptable to both Washington and key Gulf capitals and, unusually for Pakistan, relatively stable.

Pakistan’s new Middle East role carries regional implications also, particularly in relation to India. New Delhi’s strategic calculus toward Pakistan is shaped less by the country’s civilian leadership than by the perceived intentions, capabilities and red lines of its military establishment. An expanded Pakistani military footprint in the Middle East therefore feeds directly into India’s threat perceptions and deterrence planning.

This underscores how external partnerships have enabled the military to consolidate its grip on Pakistan’s domestic power structure, while simultaneously posing a challenge to its regional arch-rival, India.

Pakistan’s new security role in the Middle East is unfolding without a corresponding economic foundation. Islamabad recognises that meaningful economic recovery runs through the Gulf, this time with hopes pinned on large-scale, transformative investment rather than short-term financial relief.

In 2023, Islamabad established the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), a hybrid civil–military platform designed to fast-track foreign investment from friendly countries, particularly GCC states. The inclusion of the army chief in its apex committee underscores the military’s deepening stake in economic stabilisation. Under this framework, Gulf states have announced multibillion-dollar investment commitments, yet to date, only a handful of projects have materialised on the ground.

Pakistan lacks a significant industrial footprint in the Gulf, and its knowledge economy remains underdeveloped relative to the region’s evolving economic ambitions. Expectations that new defence agreements will rapidly offset structural economic weaknesses may therefore prove optimistic. Assessments by the IMF and World Bank, recent federal budgets, and prevailing policy trajectories all point toward continued fragility in the near term. Saudi deposits and emergency assistance from the UAE offer short-term relief but also reinforce patterns of dependency. India’s Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with the UAE, meanwhile, illustrates how swiftly economic integration can reshape regional influence, an area in which Pakistan continues to lag.

Pakistan’s power elite expects security partnerships with the Gulf to deliver large-scale investment, but ambition continues to outpace the state’s capacity to provide the predictability, stability and regulatory coherence such investments require.

Pakistan possesses a professional, battle-hardened military with extensive counterterrorism experience. Its defence-industrial base has developed credible capabilities through cooperation with China, including the JF-17 fighter program. Yet these advances are constrained by structural limitations. Pakistan lacks access to advanced Western technology transfers, while Chinese and Turkish transfers remain selective. Heavy reliance on Chinese platforms narrows strategic flexibility, even as Pakistan trails regional peers in defence research, industrial investment, and high-end innovation.

A significant portion of military expenditure is absorbed by internal security operations and border management, leaving limited fiscal space for sustained technological development. National research and development spending, hovering between 0.3 and 0.4 percent of GDP for over a decade, remains among the lowest in the region.

Under these conditions, external investment and joint production are not optional but essential. This reality underpins Islamabad’s outreach to Qatar and its optimism regarding the Saudi defence agreement, viewed as a potential conduit for deeper industrial integration.

As Gulf states accelerate investments in defence localisation and advanced manufacturing, Pakistan’s ability to reposition itself as an industrial partner, particularly in drones, naval platforms, and cyber defence, will determine whether it evolves beyond the role of a conventional security provider. Absent such alignment, Pakistan’s nuclear deterrent will remain strategically significant, but insufficient on its own within the Gulf’s rapidly transforming defence-industrial ecosystem.

Challenges and vulnerabilities

Terrorism continues to drain Pakistan’s strategic bandwidth, constraining its capacity to project influence beyond its borders. Between 2022 and 2024, Pakistan ranked among the world’s most terrorism-affected countries; in 2024, it rose to second place on the Global Terrorism Index.

Renewed militant momentum, persistent tension with India along the eastern border and volatility in relations with Afghanistan impose cumulative pressure. A state managing multiple active fronts can project influence abroad only insofar as its institutions can absorb sustained strain at home.

Driven by aspirations for a broader Middle Eastern role, Islamabad has pursued domestic militancy with renewed urgency. In October, Pakistani forces conducted airstrikes in Afghanistan targeting Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan leadership, followed by intense border clashes with the Afghan Taliban that disrupted bilateral trade.

These measures, however, have yielded limited returns. Pressure on Kabul has not significantly reduced cross-border attacks, while India continues to issue threats of “Operation Sindoor 2.0.” There is little indication that Pakistan’s internal security constraints will ease in the near term.

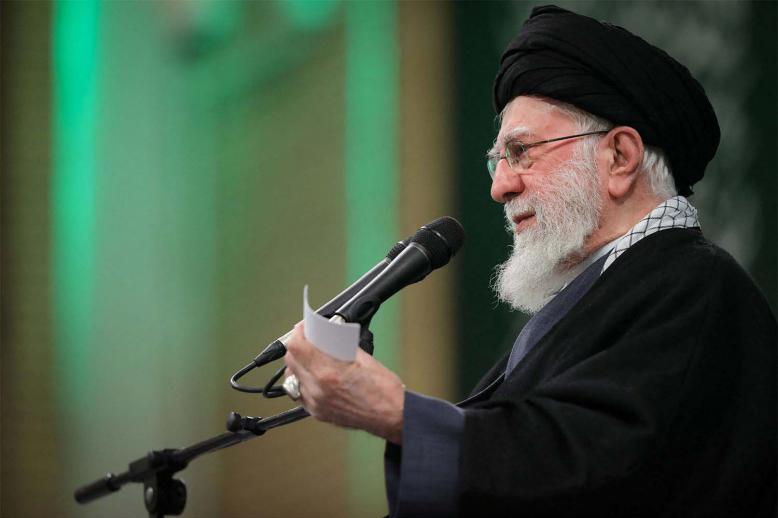

Pakistan is among the few Muslim-majority states where Middle Eastern ideological currents can rapidly reverberate through domestic politics. Recent events illustrate this vulnerability. Between October 31 and November 20, attacks killed more than ten Pakistani soldiers. A previously unknown group, Defaʿ al-Quds (Defence of Al-Quds), claimed responsibility, accusing Pakistan’s military of siding with Israel and betraying the Palestinian cause. Whether the group represents a new entity or a rebranded network remains unclear; what is evident is how swiftly Pakistan’s Middle East posture can be reframed and weaponised domestically.

Among Muslim-majority states considering participation in Gaza-related stabilisation efforts, Pakistan arguably faces the most complex decision calculus. Diplomatic incentives are clear: closer engagement with major powers. Yet political and moral risks are equally stark. An ambiguous mandate, unclear rules of engagement, or fragile local legitimacy could intensify domestic polarisation while exposing Pakistani forces to operational and propaganda vulnerabilities.

Islamabad has emphasised that it will not participate in any effort to disarm Hamas. Yet even a consensual disarmament process would likely be recast by extremist narratives in hostile terms. Any operational setback in Gaza would reverberate directly through Pakistan’s political and military leadership.

It is therefore unsurprising that the military has signalled the need for parliamentary authorisation before any final decision. This approach distributes political responsibility and ensures that no single institution bears the full burden of a potentially divisive choice. Pakistan’s long experience in UN peacekeeping lends it credibility in stabilisation missions. Gaza, however, is not a conventional UN operation. Sensitivity around the issue is widely recognised across Pakistan’s civil–military landscape.

It remains unclear whether Pakistan’s potential participation would reflect strategic autonomy or external pressure from Washington. Either choice carries risk: refusal could limit Pakistan’s regional influence, while compliance may deepen domestic vulnerabilities.

Pakistan’s recent opening across the Middle East and North Africa is driven less by deliberate statecraft than by shifting regional security dynamics, with a clear emphasis on defence and security cooperation. While this creates a real moment of strategic relevance, its endurance will depend on whether the state can convert it into institutional, economic, and governance reform. At the same time, the challenges surrounding Pakistan’s expanding regional role require a cautious approach and a coherent long-term strategy.