UN human rights council reviews Turkey’s abysmal record

UN set to review topics including freedom of press in Turkey, which was ranked as world’s worst jailer of journalists for three years until 2019.

Tuesday 28/01/2020

GENEVA - The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) held a meeting on Tuesday to review Turkey’s human rights record, widely criticised since a 2016 failed coup attempt led to government crackdowns.

The UN review is aimed at examining human rights trends over a wide variety of topics including hate crimes, freedom of the press and LGBT rights.

Over the four years since the thwarted attempt to topple President Erdogan’s government, Turkish authorities used heightened powers during a state of emergency to detain thousands of activists, political opponents, and journalists on vague and broad charges.

The crackdown hit civil society workers and members of the press particularly hard, with 130,000 public officials dismissed by decree, along with hundreds of journalists, illustrated by The Committee to Protect Journalists’ ranking of Turkey as the worst jailer of journalists in the world for three years running until 2019.

“No state or power can decide who is a journalist, it is the domain for professional organisations and should always be separate from power,” Ahval editor-in-chief Yavuz Baydar said at the IOHR panel.

The Turkish government, in a report submitted to the UN before the review, called for the coup attempt to be considered in order to “accurately reflect on the period under review” and “put things into their full context”.

Emergency power

Following the violent coup attempt of July 2016 in which 250 people died, Erdogan’s government immediately blamed the Fetullah Gülen movement, which Turkey deems a terrorist organisation, and whose leader lives in self-imposed exile in the Unites States.

Under the umbrella of emergency powers, anybody with alleged links to the Gülen network has since been swept by the ongoing purge, which most recently manifested in the call to arrest of 176 members of the armed forces in early January.

According to Turkey’s report, a state of emergency was declared “in order to ensure the continuity of the Turkish democracy and to protect the rule of law, rights and freedoms of (Turkey’s) citizens”.

However, critics of Erdogan’s Justice and Development party (AKP) say that the government used broader emergency powers, an end to which was postponed multiple times, in order to destroy political opposition.

Control over the mainstream press has created a precarious arena for journalists, who are fearful that criticism of government decisions, such as their operation against Kurdish militias in Syria, is equated to a crime.

“We are censoring ourselves because of these fears,” activist and Ahval contributor Nurcan Baysal said at a panel organised by the International Observatory of Human Rights (IOHR) and the Press Emblem Campaign the day before the UNHCR review.

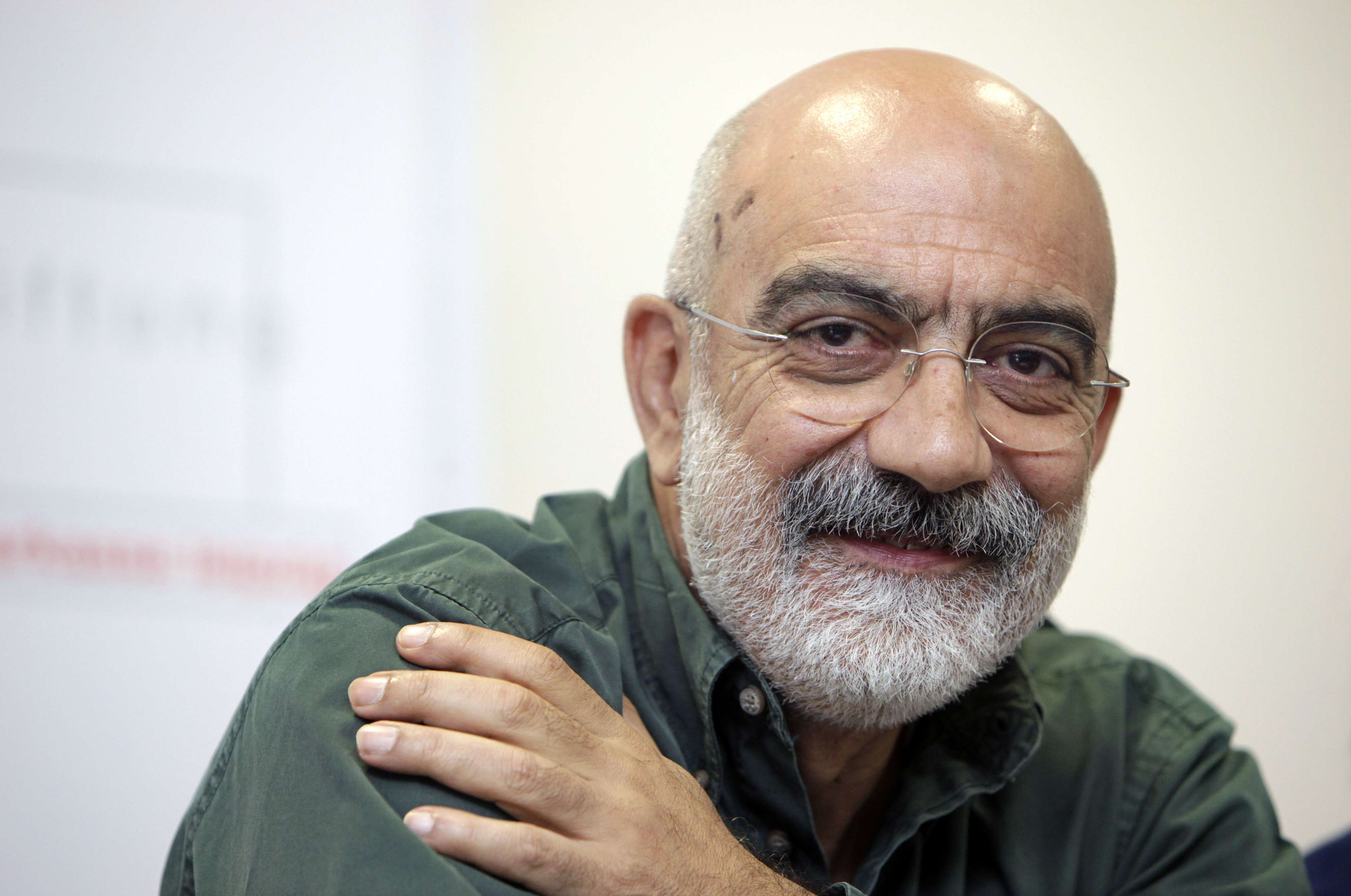

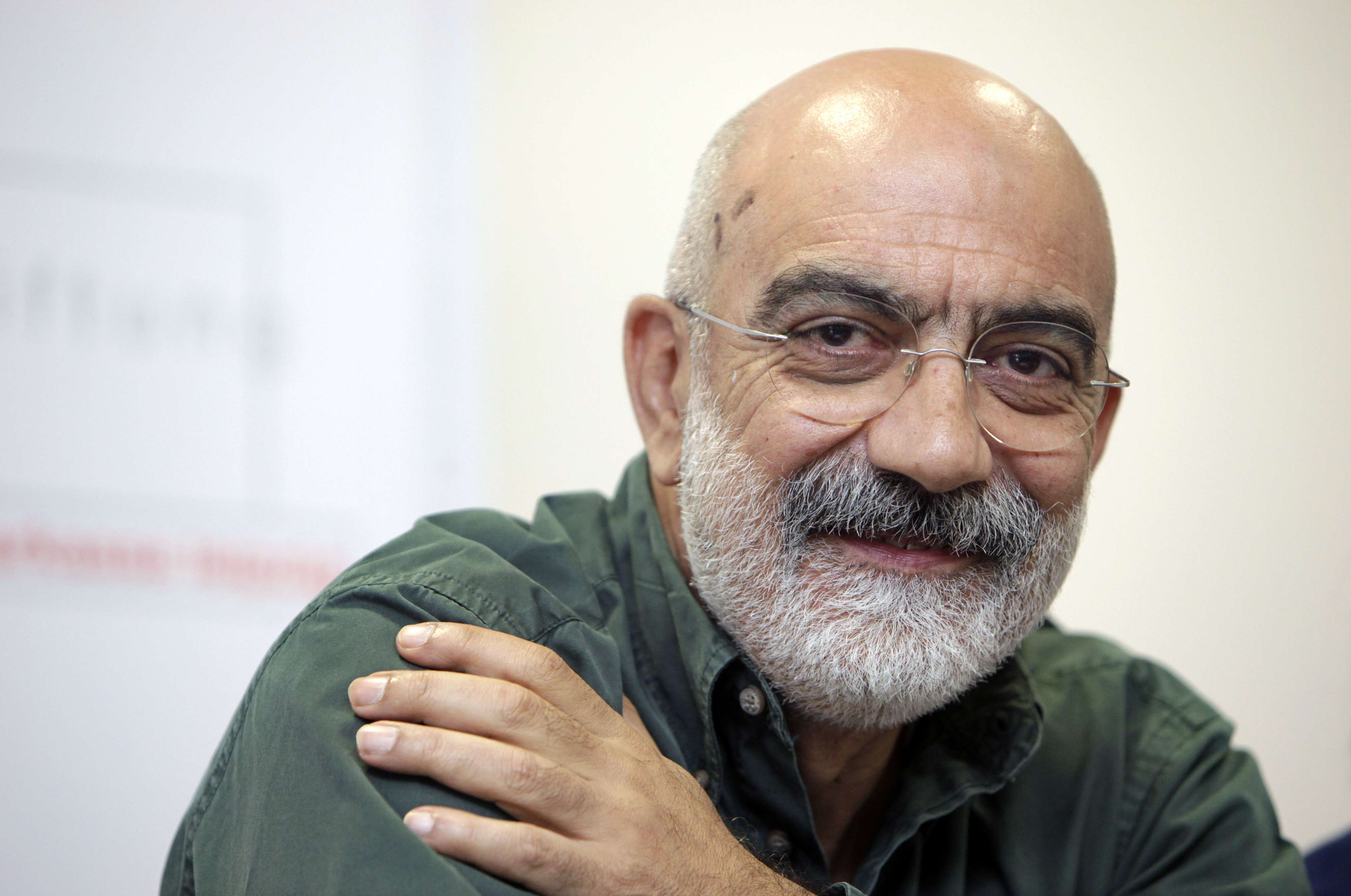

Prominent journalist and author Ahmet Altan remains in prison on coup-related charges for articles he wrote, along with many others.

“For example, before coming here I asked myself if I should use certain words, should I use the word invasion, or should I use the word war, because today in Turkey even to say war is forbidden,” she said. “Everything that I say has an effect on not only my life, but of the lives of my children and family.”

Prominent journalist and author Ahmet Altan remains in prison on coup-related charges for articles he wrote, along with many others.

Turkish government envoy Faruk Kaymakçı defended the crackdowns by saying that propaganda for terrorism should not be covered by a right to freedom of expression, and that Gülen members were posing as journalists.

Erdogan also used the post-coup period as an opportunity to boost his power with a new presidential system, removing oversight and bringing the judiciary under executive control, drawing more ire from rights groups.

Courts have been handing out lengthy sentences and fines to political figures and civilians for social media posts, supporting Erdogan’s policy of silencing dissent.

An Istanbul court sentenced the chair of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), Canan Kaftancıoğlu, to over nine years in prison for charges including insulting the president on social media.

The President of the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey Şebnem Korur Fincancı told the IOHR panel that rights violations had become commonplace because “all the procedural safeguards have been neglected”.

The UNHCR is set to announce their recommendations on Thursday.