Why 2026 could be the year the Western Sahara dispute finally ends

As 2026 begins, the Western Sahara file is entering a markedly different international and UN context from that which defined the dispute for decades. This shift is not accidental. It is the product of diplomatic gains accumulated by Morocco over the course of 2025, alongside substantive changes within the UN Security Council that increasingly favour Rabat’s approach to closing what it regards as an artificial conflict, an approach grounded, as King Mohammed VI has long argued, in political realism and workable solutions.

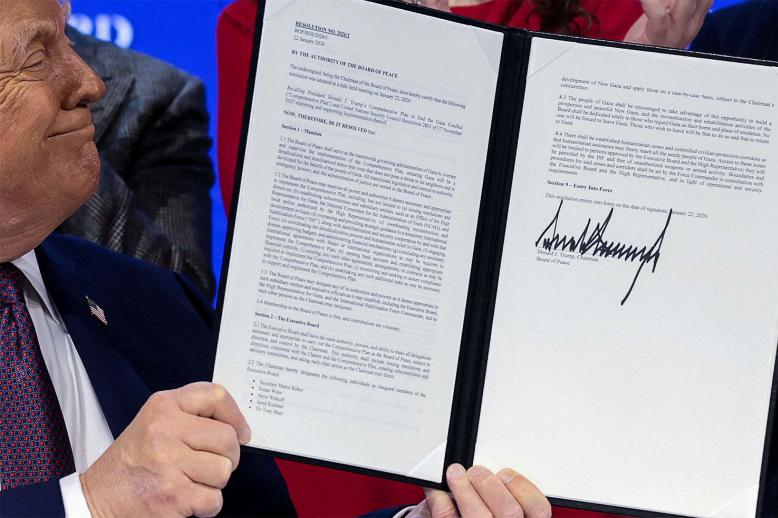

The turning point came in October 2025, when the Security Council adopted Resolution 2797, one of the clearest and most consequential texts since the UN process began. The resolution endorsed Morocco’s autonomy initiative as the serious, credible and realistic basis for any future political settlement, while also settling a long-contested question: Algeria was named a direct party to the dispute, not a neutral observer. In doing so, the Council placed Algiers squarely before its responsibilities, urging engagement at the negotiating table rather than influence exercised from the sidelines.

Algeria’s role has never been a secret. For years it has provided political, financial and military backing to the Polisario Front, pressing the separatist case under the banner of “self-determination,” a principle it firmly rejects when applied to its own territory, notably in Kabylie, where the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK) movement advances the same claim.

The gradual reorientation of UN language towards Morocco’s position did not emerge in a vacuum. It reflects sustained Moroccan diplomacy, built on foundations laid by King Mohammed VI, that has shifted the Sahara issue away from ideological confrontation and towards pragmatic political resolution. Rabat has capitalised on changing global power balances and a growing international fatigue with frozen conflicts that drain regional stability without offering a credible path forward.

The composition of the Security Council in 2026 further strengthens this momentum. Five new non-permanent members, Bahrain, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Liberia, Latvia and Colombia, have taken their seats. For Morocco, this matters. Bahrain, the DRC and Liberia not only recognise Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara but have given that recognition tangible form by opening consulates in Laayoune and Dakhla, a move with considerable political and legal weight within the UN system.

With this bloc of openly supportive states inside the Council, Morocco’s diplomatic capital is reinforced, while the room for manoeuvre by opposing parties narrows. This comes amid sustained backing for the autonomy framework from three permanent members, even as separatist arguments retreat into a largely defensive posture within UN corridors.

Timing, too, may prove decisive. Bahrain will assume the rotating presidency of the Security Council in April, coinciding with the secretary-general’s regular briefing on the political process. For Rabat, the alignment is favourable: Manama’s firm support for Morocco’s territorial integrity could help foster a constructive political atmosphere consistent with the momentum generated by Resolution 2797.

In October, Greece will hold the presidency, when the Council is expected to debate and adopt a new resolution on the Sahara. Morocco is banking on its stable and improving relations with Athens, as well as the diplomatic window between now and then, to consolidate existing gains and anchor autonomy as the definitive settlement framework.

All of this unfolds against a broader international backdrop marked by mounting pressure to resolve long-running regional disputes. In an increasingly volatile global environment, defined by geopolitical rivalry and a diminished UN capacity to manage open-ended crises, the appetite for indefinite stalemates is waning.

Morocco’s autonomy proposal aligns neatly with these priorities. It offers a practical solution that preserves stability, enables local development and promises an end to the prolonged hardship of Sahrawis living in the Tindouf camps under Polisario control.

The indicators suggest that 2026 could mark a decisive phase in the Sahara dossier, perhaps even its final chapter. Morocco’s diplomatic drive shows no sign of slowing, while the Security Council appears increasingly inclined towards Rabat’s realist framework, coupled with greater pressure on those obstructing meaningful engagement.

In this context, talk of closing the file altogether no longer sounds like diplomatic optimism. It reads instead as a plausible scenario, one underpinned by shifting power balances, evolving UN dynamics and a settlement that is Moroccan in design, international in legitimacy and broadly accepted on the world stage.